| |

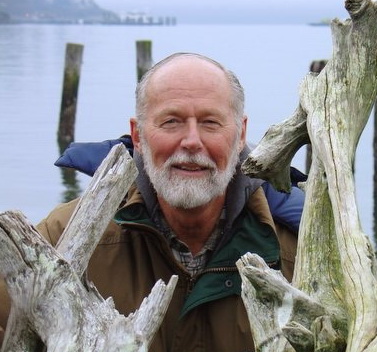

Dr. Robert D. Crane

Director, Center for the Study of Contemporary Muslim Societies, Qatar Foundation; Director for Global Strategy, The Abraham Federation; Co-Founder, Center for Economic and Social Justice, www.cesj.org GHA Vice-president Doha, Qatar

In Russian: http://www.peacefromharmony.org/?cat=ru_c&key=546

Bio

Robert Dickson Crane

Robert Dickson Crane, also known as Faruq 'Abd al Haqq, has been a life-long expert in long-range global forecasting for government and industry, with professional work ranging from his Directorship for Third World Studies from 1965 to 1968 at the Hudson Institute to his current position in 2012 at the Qatar Foundation in Doha as Director of the Center for the Study of Contemporary Muslim Societies.

On September 4, 1962, he became one of the four co-founders of the first foreign affairs think-tank in Washington, the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He was the principal foreign policy adviser from 1962 to 1967 for Richard Nixon, who in January, 1969, apppointed him Deputy Director for Planning in the National Security Council. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan appointed him U.S. Ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, responsible also for two-track diplomacy with the Islamist movements in the Middle East and North Africa.

His academic career included earning a B.A., summa cum laude, in 1956 from Northwestern University in Sino-Soviet studies with a 4.0 GPA and a J.D. in 1959 from Harvard Law School in international investment, where he served as the founding president of the Harvard International Law Society and editor-in-chief of its journal, and headed a project for the U.S. Supreme Court on the constitutionality of international law. He also spent one year at the University of Munich, Germany studying the sociology of comparative religion. He served from 1960 to 1965 as an Associate and later as Counsel of the world's leading communications law firm, Haley, Wollenberg, and Bader.

Since 1982, Dr. Crane has worked as head of his own think-tanks on developing global ethics as a framework for peace, prosperity, and freedom through the interfaith harmony of normative and compassionate justice. In this capacity he has published several hundred professional articles and four books primarily on normative Islamicjurisprudence, including the first textbook ever written on Islam and Muslims, an 800-page, two-volume work that he and Mohammad Ali Chaudry completed in 2011 as the Chairman and President, respectively, of the Center for Understanding Islam.

July 7, 2012 -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Creeping Shari’ah and Galloping Secularism: The Mimetic War between Perennialist ontology and Secularist Epistemology in the Arab Spring and the Global Awakening by Dr. Robert D. Crane Part I: Jurisprudential Metaphysics: Posing the Problem The issue is human rights.Where they come from is just as important as construing what they are or might be.In mid-June, 2012, this issue of whither, what, and whence produced a veritable book of debate in the sociology-of-Islam listserve. De Gustibus non est disputandem. “There is no disputing taste”. Much of the discussion reflected paradigmatic preferences as matters perhaps of simple tastes.The master of mimetics, Professor Muhammad Fadel, who, as a Wall Street attorney, founded Muslims Against Terrorism in New York City immediately after 9/11, introduced the dichotomy between “creeping shari’ah”, which is the beloved phrase of in-your-face Islamophobes, and “creeping secularism”, which is its opposite, though the jury is still out on which is creeping the fastest. When the discussion began to focus on the field of governance as the focus of current interest in human rights, if not as the origin of human rights as a discrete field of knowledge, Professor Fadel identified respect for minority rights as a major criterion for deciding between monarchy/oligarchy and majoritarian democracy (either one-man-one-vote or one-dollar-one-vote) as a preferred political system. Perhaps this is a matter of taste, because both are distasteful. The degree of distaste may depend on whether one argues within the perennialist or the positivist perspective. The perennialist paradigm is best illustrated by the shelf of books by Hossein Nasr, who represents the turath or heritage of Persia and America, as well as by the very similar paradigm of the Scottish Enlightenment represented by Edmund Burke, the leader of the minority Whig Party in the 18th century English Parliament, who was the mentor of all of the Founders of the Great American Experiment in just governance. They both accepted monarchy with limitations, but, like Aristotle, both feared French Revolutionary democracy as the worst form of government. Jefferson’s attack on the British monarchy in his first draft of the American Declaration of Independence, was one of the only two parts of this document deleted by the Continental Congress (the other being ironically his denunciation of human slavery as the worst of all abominations). The perennialist paradigm is essentialist, meaning that ontologically it exists independently of context, and is based on the premise that truth is absolute. It is the epistemological task of the human intellect to understand enough of it to derive principles of justice both from divine revelation and from the aspects of natural law that can be deduced from observation of the laws of the universe, including human beings. It is the further task of human governance, preferably through an elected legislature, to translate these ideal jurisprudential principles into practical guidance. If the specific laws have to be enforced, then the entire exercise has failed in its primary purpose, which is education. The key is that man does not invent truth, though he may derive universal principles of global ethics from whatever glimpses he may receive from the ultimate or what Meister Eckhart and Hans Kung have called “beyond being”. The modern positivist paradigm, on the other hand, is best illustrated by Austinian jurisprudence, which I think was invented at Harvard Law School shortly after the American Civil War.This is why the main building there is named Austin Hall. In contrast, a strictly secondary building is named after Supreme Court Justice Story, who championed natural law immediately before the Civil War as a holdover from the time of the Founding of the United States of America. He was weakened by the fact that the Southern Confederacy used natural law and the Bible to defend slavery. Positivist law consists of whatever human beings posit as the law of the land. In order to avoid the natural tyranny that could result from such a paradigm, the supporters of positivist law emphasized an implied contract between the people and the government, which itself was based on the spectrum of contract theorists, best illustrated by Locke, Hobbes, and Rousseau, who exercised only a minor influence on America’s Founders but conveniently provided a fall-back position. Professor Fadel supports the Rawlsian position, which warns against the danger of “comprehensive doctrines” of either perennialist/conservative or classically liberal persuasion. He prefers, therefore, a restrained liberalism limited to political constitutionalism applying to governance, especially in the era of the modern state, which recognizes no authority above its own and certainly not the authority of any transcendent absolute. At the individual level, as well as at the level of civil community, Rawls relies on the reasonableness of the majority of citizens to order their own lives. This assumes that the particulars of justice will be developed and respected in ways perhaps unique to each person and civil union. This might be considered to be realistic utopianism or what I would prefer to call idealistic pragmatism as essential in all private and public life. This dichotomous paradigm of harmony between the political universal and the moral particular can provide a basis for developing a common language for the spectrum of citizens who in most Arab countries oppose the imposition of values by either the Salafist “right wing” or the “socialist left wing”, but are also realistically suspicious of the Ikhwan or Muslim Brotherhood. Underlying any idealistically pragmatic solution to avoiding a pendulum swing back and forth from tyranny to chaos and back to tyranny is the problem of defining the terms that are bandied back and forth, whereby each appendage of the many-sided hydra on the street claims the same mimetic symbols as its own. This reminds one of the “first martyr on Tahrir Square”. Six different competing groups claimed her as the soul of the revolution, despite the fact that reporters subsequently established that she had never even been there. This is the art of mimetic warfare. Whoever can capture the dominant mimes in the form of either visual or oral symbols (e.g. placards, music, and poetry) has an advantage in shaping thought and action. In the discussions at the conference on the Arab Spring held at the end of May and the beginning of June, 2012, at the Qatar Foundation by its Center for the Study of Contemporary Muslim Societies and its partner, St. Antony’s College of Oxford, four representative mimes were advanced.These are asabiya, khilafa, dawla, and democratia. Depending on how one defines them, each can be seen as posing the threat of what Muhammad Fadel, using the metaphor of “mission creep” evidenced in Iraq and Afghanistan, calls “shari’ah creep” and “secularism creep”. The question is whether the phenomena of creeping extremism of all kinds will morph into galloping chaos, or whether these terms can be reinterpreted to become part of a common language for the moderate middle, the wasatiyah. Part Two Mimetic Challenges to Developing a Common Language I. Asabiya The terms, asabiya, khalafah, dawla,and democratia, constitute symbols that embody entire frameworks of thought. They can be manipulated through the art of paradigm management to either expand or limit the human mind subliminally so that the target audience is unaware of the imposed blinders. The most powerful force in the various springs that emerged in the Year 2011 all over the world is the demand for dignity and respect. At its root the search is for what John Paul II called “personalism,” which involves both respect for the individual person as the purpose of human governance and reliance on the individual to perfect the group. Equally important is respect for the group or community all the way from the nuclear family to the nation. We may define the nation as a group with a common heritage, common concerns in the present, and common hopes for the future, usually with a common language and sometimes with a common majority religion. This is what Ibn Khaldun called the good asabiya or community loyalty, but the term nowadays generally is used pejoratively to justify secular statism and nation-building without nations as organic communities. The opposite is the bad asabiya, which is defined as tribalism, especially religious tribalism. Tribalism consists of pride in oneself and one's own tribe at the expense of other tribes and even in denial of all human rights except one's own. The good asabiya consists of pride in the best of one's own tribe with openness to share whatever wisdom one has with other tribes in order to cooperate for the common good. The good asabiya goes beyond mere tolerance, which means essentially, “I won’t kill you yet”. It goes even beyond tolerance to diversity, which means, “You are here and I can’t do much about it”. Finally, it extends to pluralism, which means, “We welcome you, because we each have so much to offer each other”. The good asabiya can extend still further to respect not merely for individuals but for their religions. God created humans with diversity of language, cultures, communities, and even religions so that we as persons and as members of unique communities can get to know each other and thereby cooperate for everyone's mutual benefit. Critics of “nationalism” contend that the construction of a polity on national lines, if it means a displacement of the Islamic principle of solidarity, is simply unthinkable to a Muslim. This is correct, but equally valid is the principle that solidarity in recognizing and respecting universal human responsibilities and human rights makes construction of a polity without nations Islamically unthinkable. Islamic asabiya is the basis for federations or confederations of nations within a state or at a higher regional level. The Qur'anic principle of tawhid provides for diversity in the created order so that the coherence of diversity will point to the oneness of the Creator. Otherwise there would be only one standard tree, one standard flower, and one standard sunset, and therefore one standard human. The attempt to standardize humans and humanity therefore is the worst of all polytheisms. II. Khilafah Another term that requires understanding if it is to provide productive guidance, rather than serve as a barrier and challenge to communication and cooperation, is the “Islamic Caliphate”. Ideally this is based on the principle of khilafah, whereby every person, including both the rulers and the ruled, are responsible first of all to God as stewards of Creation. This means that the institution of the caliphate is not military or political in nature but instead consists of the ijma or universal consensus of the wise persons and scholars on the nature and application of justice, which one might call the academic discipline of 'Ilm al 'Adl. This is based on the Qur'anic verse, wa tama'at kalimatu rabika sidqan wa 'adlan, (Surah al An’am, 6:115), "The Word of your Lord is completed and perfected in truth and justice". The most articulate and assiduous of the scholars on the meaning of the Islamic caliphate was Ibn Taymiya, who lived at the time of the Mongol invasion. Some Muslims, notably the Hanbalis, claim to honor Ibn Taymiya as their mentor, but they distort his most essential teachings. For example, many Muslims condemn Sufism as inherently un-Islamic, but they seem to be unaware that Ibn Taymiya was a Sufi who condemned the Sufi extremism that was spreading as a populist movement in his day. He also was an ardent supporter of the khilafahbut not as an institution of military or even political governance. Salafi extremists, among whom Osama bin Laden was the most famous, claim that Ibn Taymiya supports their call for a one-world government under a single Caliph. In fact, Ibn Taymiya developed a sophisticated understanding about the Islamic doctrine of the khilafahthat demolishes the extremists of his day and of ours. Ibn Taymiya was a political theorist who was imprisoned by the reigning Caliph and died in prison ten years later for opposing the extremism both of tyrants and of their opponents. He was in fact a model of those who both understand the sources of extremism and the means to counter it. His mission was to deconstruct extremist teachings doctrinally in order to marginalize their adherents. One of his modern students, Naveed Shaykh, in his The New Politics of Islam: Pan-Islamic Foreign Policy in a World of States, London: Routledge Curzon, 2002, writes rather poetically that extremism comes when pan-Islamists “operationalize a unity of belief in a human community of monist monolithism rather than in a boundless love for all of God’s creation in a transcendent Islamic cosmopolis.” Extremism comes when people substitute a political institution for themselves as the highest instrument and agent of God in the world, when they call for a return of the Caliphate in its imperial form embodied in the Ottoman dispensation. It comes when they call for what Shah Wali Allah of India in the 18th century called the khilafat zahira or external and exoteric caliphate in place of the khilafat batina or esoteric caliphate formed by the spiritual heirs of the prophets, who are the sages, saints, and righteous scholars. In the late Abbasid period of classical Islam, according to Naveed Sheikh, “The political scientists of the day delegitimized both institutional exclusivism and, critically, centralization of political power by disallowing the theophanic descent of celestial sovereignty into any human institution.” In other words, they denied the ultimate sovereignty claimed by modern states since the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, which elevated states to the ultimate level of sovereignty, in place of the divine, thereby relegating religion to the periphery of public life or excluding it and with it morality altogether. The late Abbasid scholars, faced with a gradual process of creeping despotism, denied the divine right not only of kings but of every human institution, and they condemned the worship of power and privilege that had brought corruption upon the earth. For insisting on this foundation principle of Islam, the greatest scholars throughout Muslim history were imprisoned, some for years and decades. See Chapter 59 of Khalid Abou el-Fadl, “The Scholar’s Road,” in his book, Conference of the Books: The Search for Beauty in Islam, Lanham, MD, University Press of America, 2001. This is precisely why Muslims traditionally have considered them to be great. Ibn Taymiya completed the process of deconstructing the ontological fatalism of caliphatic thought by restricting the role of the caliphate to what perhaps the greatest Islamic thinker of all time, Abu Hamid al Ghazali, had called an ummatic umbrella functioning only to protect the functional integrity of Islamic thought rather than to govern politically. Ibn Taymiya asserted that the unity of the Muslim community depended not on any symbolism represented by the Caliph, much less on any caliphal political authority, but on “confessional solidarity of each autonomous entity within an Islamic whole.” In other words, the Muslim umma or global community is a body of purpose based on worship of God. By contending that the monopoly of coercion that resides in political governance is not philosophically constituted, Ibn Taymiya rendered political unification and the caliphate redundant. The principal proponents of the esoteric caliphate, the khilafat batina, have been the Shi’a scholars, because they were the most oppressed of the oppressed under the most un-Islamic of the Muslim would-be emperors. This may explain why they have always emphasized that purpose takes priority over practice, meaning that the legitimacy of practice must be determined by higher purpose. III. Dawla and Democratia Many Muslims often refer to “the Islamic state” as a goal of the Arab Spring. Such a concept is un-Islamic because an Islamic state is an oxymoron. Others refer to the state in the Western sense as dawla.Better might be the terms Islamic society or community or system of governance. The best term to use is "Islamic polity", fully recognizing that there is no such polity in existence today and may never be. There are many Muslim states, defined as countries with a Muslim majority, but few, if any, of them qualify to be Islamic. This distinction is captured by contrasting Christianity with Christendom and Islam with Islamdom. The concept of the state did not exist in all of human history until the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 ended the "Thirty Years War" in Europe between the Roman Catholics and the Lutheran Protestants. In order to end the war, the contending parties agreed that forever more political authority would not come from any higher authority beyond humans, and that human power alone would determine what is right and what is wrong. This raised the question of managing human power. Some believed in elitism, sometimes in the form of Neo-Colonialism or more recently in Neo-Conservatism. Others proposed so-called democracy, usually in the form of "winner take all", whereby a 51% majority of a vote was the only legitimate source of both law and ethics, though others advocated proportional representation in order to avoid the tyranny of the mob over minorities. America’s Founders deleted Jefferson’s opposition to the British monarchy from his first draft of the Declaration of Independence, because they were more concerned about what James Madison called the “elective despotism” of the mercantilist parliament. The term "Islamic state" is an oxymoron, because the institutionalization of human will as the highest source of truth is the exact opposite of Islam and of all the world religions. Unfortunately, the historical practice of Islamdom and Christendom shows that the norm was the same as today, namely, "might makes right". America's founders believed that "right makes might". They universally condemned democracy as the worst form of government, as did Aristotle, because they associated it with the anarchy and subsequent totalitarianism of the French Revolution, which gave rise to Communism, Nazism, and modern Zionism. The same may be the demise of the Arab Spring or any other spring in Iran, China, Russia, or even in America, unless it becomes more principled. At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, according to the notes of James McHenry, who was onc of Maryland’s delegates, Benjamin Frabklin was asked, “What have we got, a republic or a monarchy”?”He replied, “A republic, if we can keep it”.A republic by definition recognizes that natural law provides the ultimate source of values and legitimate legislation. Natural law is a combination of divine revelation, scientific observation of the laws inherent in the physical world, and rational thought to understand the first two elements of a higher reality. The drafter of the American Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, emphasized education in virtue as the basis for responsibility of the person and community for a divinely inspired society of faith-based freedom. This basis for a just society eliminates sectarianism and any effort to impose religion by political or any other pressure, which could be the natural result of the worst form of government, namely, a democracy. The common wisdom of classical American and classical Islamic thought consists of recognition that both Islam and Christianity call for a republic, which by definition condemns the amoral and usually immoral institution of the state. A more generic term suitable for a republic is "polity", which is the term increasingly used by experts in jurisprudence. An Islamic polity can be described perhaps best as a community or nation and an economic and political system of governance that respects the human responsibilities and human rights enshrined in the classical understanding of the normative principles of Islamic jurisprudence, namely, what Hans Kung at the Second Parliament of the World Religion in Chicago in 1993 introduced as “global ethics” and what the present author as a minority of one in the Muslim delegation translated as the essence of the maqasid al shari'ah. Three of the eight irreducible, normative principles known in all world religions but best expressed in the maqasid al shari'ah are: 1) haqq al nafs, which requires respect for the sacredness of the individual person created with a purpose by God; 2) haqq al nasl, which requires respect for the community from the nuclear family all the way to the nation, because it consists of sacred individuals who in solidarity have a divinely designed purpose; and 3) haqq al hurriyah, which requires respect for political self-determination (political freedom) through the institutionalization of khilafa, shurah, ijma, and an independent judiciary. This political self-determination presupposes economic self-determination, based on the principle of subsidiarity, which provides that all problems must be addressed at the lowest level and may be addressed at higher levels only when the lowest level cannot solve them. In a capital-intensive economy, this requires broadened and even universal and equal access to individual capital ownership through the institution of credit based on future profits from capital investment rather than exclusively from credit based only on past wealth accumulation, as pragmatically explained in detail in the books and hundreds of articles available at www.cesj.org. This bottom up, rather than top-down, ordering of society requires spiritual awareness and social solidarity at each of the lowest levels of community in order to shape the institutions of society as guardians for the ordered freedom of the individual. Without such freedom and community solidarity in promoting respect for human responsibilities (both fard 'ain and fard kifaya, i.e., both personal and social responsibilities), political governance cannot protect the individual person from the imposition of order by elites and from the denial of human rights. These four terms basic to Muslim usage in discussing the past, present, and future of the Arab Spring, namely, asabiyah, khilafa, dawla, and democratia, require general agreement on their meaning if what began as a “spring” is not to end up in an “Arab Winter”. The first requirement of a revolution is to go beyond the stage of simple revolt in order to engage the substance of enlightened change by seeking peace, prosperity, and freedom through the interfaith harmony of compassionate justice for everyone. June 14, 2012 ==================================================

QFIS-Arab-Spring-Common-Language-April-11-2012 The Arab Spring: Developing Unity through a Common Language of Normative and Compassionate Justice by Dr. Robert D. Crane[1]