| |

How Sociocybernetics Can Help Understand Possible World Futures[i] Bernard Scott Center for Sociocybernetics Studies, Bonn bernces1@gmail.com, bernard.scott@sociocybernetics.eu Personal page: http://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=255 Introduction Sociocybernetics is concerned with applying theories and methods from cybernetics and the systems sciences to the social sciences by offering concepts and tools for addressing problems holistically and globally. Cybernetics is a transdiscipline (Latin “trans” - across) that abstracts, from the many domains it adumbrates, models of great generality. Such models serve several purposes: they bring order to the complex relations between disciplines; they provide useful tools for ordering the complexity within disciplines; they provide a “lingua franca” for inter-disciplinary communication; they may also serve as powerful pedagogic and cultural tools for the transmission of key insights and understandings to succeeding generations. However, as noted by Immanuel Wallerstein (1997), past President of the International Sociological Association, if a transdisciplinary approach is to make a real contribution in the natural and social sciences, it must be more than a list of similitudes. It must also be epistemologically sophisticated and well-grounded. Cybernetics, with its explicit distinction between first order studies of observed systems and second order studies of observing systems, can claim, not only to satisfy this criterion, but also to be making significant contributions to epistemological debates. This paper sets out some ideas about how sociocybernetics can contribute to understanding possible world futures. A central concept in cybernetics is ‘governance’, the art of steersmanship. As conceived by Ashby, Beer and others, this art is concerned with the management of variety. How do we face the challenge of managing all the variety that makes up ‘possible world futures’? The distinction between first and second order studies makes clear there are two levels to this challenge: 1.The variety and complexity of first order observed systems 2.The variety and complexity of second order systems, of interactions between observing systems. Already, the distinction between the two levels has reduced variety. Attempting to understand possible world futures, with studies only at level 1, omits the challenge of bringing about change through social action. Using level 2 studies to address the challenge of bringing about change through social action can only be fruitful insofar as relevant models and data are available from level 1studies. The paper briefly overviews what some current level 1 models and data are telling us about possible world futures. The paper also briefly overviews what some current level 2 models and data are telling us about possible world futures. The paper goes on to outline ways in which sociocybernetics can address the problems thus summarised. Being holistic about global problems One of the founding predications of the cybernetics and systems movement is that systemic problems need to be addressed holistically (Beer, 1967). I discussed the question of what it means to be holistic about global problems in Scott (2002). I quote: ‘With respect to the need to be both holistic and global, Luhmann (1989) very clearly warns of two dangers: (i) failure to “resonate” with the ecosystem (not being global enough in our concerns); (ii) ...... too much resonance between social systems (not being holistic enough to dampen unfruitful noise and “excitement”). ‘Examples of (i) are many: being parochial with respect to one’s own ecological niche; focussing on one issue (e.g., “global warming” or “poverty”) but not taking cognisance of related issues (e.g., “opportunities for education” or “political freedoms”). Examples of (ii) are also many: the promotion of one scientific discipline over another; the promotion of one political ideology over another. ‘(However,) “being holistic” lacks meaning for an individual if the implied theoretical ideal lacks a praxis… Actualising holism requires a “nucleation”, a cognitive/affective centre around which the many facets and levels of our concerns may cohere as insight and intuition. .. I argue that it is precisely the perceived need for a holistic “centring” that may serve as such a centre. As practitioners it is sufficient to intend to be holistic – and to share that intent - in order for ideas to be created fruitfully.’ Sociocybernetics offers guiding principles that bear on the question of how a community of observers can establish and maintain consensus, including: 1.Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety: only variety can control variety 2.Scott’s principles of observation: there is always a bigger picture; there is always another level of detail; there is always another perspective. 3.von Foerster’s ethical imperative: act to maximise the alternatives 4.von Foerster’s corollary to his ethical imperative: A is better off when B is better off. First Order Problems Modern economies are based on forms of capitalism where returns on investment lead to reinvestment with the goal of continued economic growth. This growth requires a source of labour, much of it skilled and professional, to keep it going, together with the reinvestment of profits and readily available sources of energy and raw materials. With this growth the rich get richer and continue to do so. The so-called developed world (e.g., Europe, US, Canada, Australia, Russia) sustains its economic growth by (i) reinvestment and (ii) large scale immigration. The so-called developing world (e.g., South America, India, China and the Pacific Rim) have large populations to support economic growth and, as they develop, also attract and encourage economic migrants. Both developed and developing nations are investing in education and training and are creating relatively wealthy middle classes and super-rich plutocracies. There is a flow of labour, as legal and illegal immigrants from Africa, Eastern Europe and Asia enter Western Europe. There are flows from South America into North America. There are flows into Australia. The switch from hunter gatherer societies, over millennia, together with a growth in world population, has made humankind net consumers of the earth’s resources. That is, in the long term economic growth is not sustainable. Forests are cut down, species are lost, oceans are depleted of fish stocks, fertile lands become deserts.

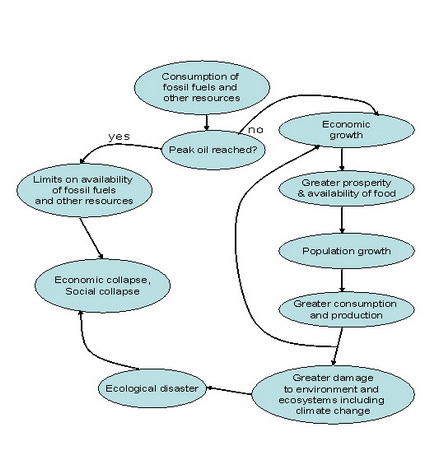

In recent times, fossil fuels, as a source of stored energy and desirable by-products such as fertilisers, plastic and pharmaceuticals, have fed economic growth and continue to do so. The use of such fuels and other resources has triggered climate change, widespread pollution and damage to the ozone layer. The problems associated with continued economic growth are exacerbated by continued population growth. It has been estimated by some that it would take five earths to support the current population if everyone was enjoying the same standard of living as that now enjoyed by ‘developed’ parts of the world. In March, 2008, a conference on the topic From Global Warning to Global Policy was convened by the World Political Forum and the Club of Rome and chaired by President Mikhail Gorbachev in Turin on March 28-29 2008. I quote from the final statement. ‘The participants concluded that the world has entered a period in which the dramatic scale, complexity and speed of change caused by human activities threaten the fragile environmental and ecological systems of the planet on which we depend. It is urgent therefore that the world community should agree rapidly on strategies and effective action to avert irreversible change in world systems, brought about by accelerating climate change, the ecosystems crisis, the depletion of energy resources and the diminishing availability of water, the degradation of environments across the world, persistent poverty and deprivation and the rising gulf between rich and poor within and between countries. Also, global population is in the midst of a transition from explosive growth to a new paradigm of development, never before experienced by humankind.’ Figure 1 is intended to be a simple holistic overview of what some current first order models and data are telling us about possible world futures.

Figure 1. An attempt at a simple holistic overview of some global problems Second Order Problems Second order problems concern human behaviour and social interactions where the participants are observing systems holding beliefs with associated values, following institutionalised behaviour patterns, engaging in creative problem solving, learning and communicating, all in the pursuit of goals, some of which may be consciously articulated, some of which are the non-conscious consequences of participation in a culture and of genetic heritage. Some important second order issues are: 1.differing kinds and levels of social and cultural development, including differences in quality of life, access to health services and education, problems of identity and social conflict, for example, as set out in the hypothesis of there being a ‘clash of civilisations’ (Huntington, 1997). 2.pathological belief systems which institutionalise ignorance, prejudice, discrimination and conflict.[ii] 3.as noted by Luhmann, the problem of ‘noise’ in the ‘marketplace’ of ideas 4.the problem of empowerment for social action as in the lack of democratic forms of government and lack of access to opportunities for personal development. These problems can be summed up in terms of two cybernetic principles: 1.Evil is that which restricts the right of actors to interact (Pask, 1991) 2.Act so as to maximise the alternatives (von Foerster, 1993) The two principles are complementary. Both are predicated on two key assumptions: (i) there is a shared gene pool (ii) ‘persons’ are socially constructed. The first principle helps identify blocks and constraints. The second principle helps to guide creative, positive action. Both are, in essence, corollaries of the Law of Requisite Variety that “Only variety can control variety” (Ashby, 1956). Variety is controlled by identifying redundancies, patterns and lawfulness. Hence the importance of education (L. educare, to lead out of) and the importance of concepts that provide transdiciplinary and metadisciplinary clarity and coherence to manage the variety of theories and models in the academic market place. Cybernetic concepts can serve the latter functions. In Scott (2014), I set out some of the concepts from cybernetics which I believe should be part of the spiral curriculum that, ideally, is revisited throughout an individual’s education from primary to higher levels, at each stage with greater sophistication and detail. How humans form and maintain systems of belief is a complex business, with rational and non-rational aspects (Wolpert, 2006). Even belief systems that are rationally constructed may in the longer term turn out to be flawed and misguided. A case in point is the faith of economists in classic economic models based on the concept of equilibrium between supply and demand. Ormerod (2005) points out that failure to predict the future is endemic in the business world. The world, as a whole, continues to surprise us.

Looking for Solutions

What might be done? As economies collapse, nation states and coalitions thereof may well go on a war footing, where new orders of doing things are imposed, for example, rationing of food and energy, bans on travel, investment in alternative forms of energy supply, imposition of birth control. As noted above, hopefully there may also be an accelerated process of education, awareness raising and political empowerment that includes the recognition that some belief systems such as ‘individualism’ are unacceptable. ‘Individualism’ is the social disease, currently legitimised and encouraged in all parts of the world, of seeking, as an individual, to become rich and powerful relative to one’s neighbours. Legislative and economic practices reforms of some kind will be required. There will be (indeed, there is) also the requirement to educate, raise awareness and change belief systems. The tough question is, “How do we (humankind) change our practices while the world is falling apart?” The battle for ‘correct thinking’ has to be won as only ‘correct thinking’ in the long term leads to ‘correct action’. The populace in the developed countries with access to resources such as mass education and mass communication systems are not stupid or necessarily ignorant. They are seduced by consumerism and the lifestyles portrayed in popular entertainment. Insofar as there is a growing awareness that disasters of one kind or another are imminent, this is accompanied by feelings of alienation and disempowerment. We will need a rapid change in popular consciousness delivering the right messages as disasters strike such that politicians and corporate leaders are obliged to change their ways. It is of value for all of us, as ‘ordinary people’ to engage in discussion about these issues. There are underlying empirical and logical truths as sketched out above, that need to be understood and promulgated. The ‘right thinking’ produced by education will lead to the ‘right action’, including the action of promoting the right thinking and of commanding the means to do so. This requires educational activities to go hand in hand with the evolution of more effective means for democratic participation. The populous, made aware of what is required, must find its voice. We need positive feedback cycles where the demand for better education and more informed knowledge about what is happening and why leads to demands for even better education, knowledge sharing and ways of translating right thinking into right action. With respect to ‘right thinking’, I have identified two fallacies which I believe need to addressed and corrected: - The fallacy of the particular: “I am all right because the problems are happening some where else.”

- The fallacy of the general: “Humankind will survive somehow.”

In relative terms, Fallacy 1 was perhaps once true but is clearly false now that, globally, as noted below, “Everything is connected to everything else.” With respect to Fallacy 2, it is possibly true but, as a pious hope, can blind us to an awareness of the great cost in human lives and suffering that will be (and is being) paid as part of the survival of the species. There follows a brief listing of some aspects of possible solutions that I have come across in the literature and in the media. There is not space here to present them in any detail. I present them as a means of promoting further discussion. - Switching to renewable forms of energy.

- Using alternative forms of production and waste disposal that are truly sustainable, possibly using nanotechnologies and ‘synthetic biology’.

- Using just and humane forms of birth control to reduce the global population.

- Only interacting with the ecosystem in ways that are sustainable and healing of damage already inflicted.

- Education for social justice and quality of life, rather than for the individualism of wealth accumulation and consumerism.

- Education and legislation for empowerment as part of more effective forms of democratic government

- A move away from the economic growth emphasis of modern capitalism as embodied in ‘limited companies’, ‘corporations’ and ‘shareholders’ towards cooperative forms of institution.

- New forms of tithing or taxation that change damaging behaviours and/or release resources that can be invested in developing sustainable ways of doing things.

Concluding Comments Given the scale of the problems at both first and second order levels, it is likely that mankind is inevitably facing major disasters on a global scale. Amelioration of these disasters will, in the limit, be in the hands of whatever communities emerge and survive locally. More global solutions are thinkable. However, as these entail a radical re-appraisal and re-education about what it is to be human, it is not obvious at this stage that these global solutions are doable. It may be too late for such a global transformation of human consciousness to be achieved. It may be that, as proposed by Morrison (1999) and many others, there are intrinsic limitations on the extent to which the human species can embody the beliefs needed to ensure its survival. A majority of commentators appear to see no alternative to capitalism, economic competition, continually striving for more, for better ‘standards of living’.[iii] Some do question the values and their relative importance. What is more important; a high income or safety from harm, riches or job satisfaction? And so on. There are alternatives to secular, materialistic capitalist ways of life. For example, there those based on the concept of sustainable living, abiding by Commoner’s (1971) Four Laws of Ecology. I cite them here as key holistic, systemic, cybernetic ideas that are essential for understanding how we might manage the variety in global systems: 1. Everything is connected to everything else. There is one ecosphere for all living organisms and what affects one, affects all. 2. Everything must go somewhere. There is no "waste" in nature and there is no “away” to which things can be thrown. 3. Nature knows best. Humankind has fashioned technology to improve upon nature, but such change in a natural system is, says Commoner, “likely to be detrimental to that system.” 4. There is no such thing as a free lunch. In nature, both sides of the equation must balance, for every gain there is a cost, and all debts are eventually paid.[iv] It is my belief that ideas such as these should be vital parts of educational curricula, from the cradle to the grave. References Ashby, W.R., (1956). Introduction to Cybernetics, Wiley, New York. Beer, S. (1967). Decision and Control, Wiley, New York. Commoner, C. (1971). The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology. Knopf, New York. Huntington, S.P. (1997). The Clash of Civilisations and the Remaking of World Order, Simon and Schuster, London. Luhmann, N (1989) Ecological Communication, Polity Press, Cambridge. Morrison, R. (1999). The Spirit in the Gene: Humanity's Proud Illusion and the Laws of Nature, Cornell University Press, New York. Ormerod, P. (2005). Why Most Things Fail … And How to Avoid It. Faber and Faber, London. Pask, G. (1991). "The right of actors to interact: a fundamental human freedom", in Glanville, R. and de Zeeuw, G. (eds.) Mutual Uses of Cybernetics and Science (Vol 2), Systemica, 8, pp. 1-6, Thesis Publishers, Amsterdam. Scott, B. (2002) “Being holistic about global issues: needs and meanings”, J. of Sociocybernetics, 3, 1, pp. 21-26 (presented at the 1st International Conference on Sociocybernetics, University of Crete, May, 1999). Scott, B. (2009). “The role of sociocybernetics in understanding world futures”. Kybernetes, 38, 6, pp. 867-882. Scott, B. (2014). “Education for cybernetic enlightenment”. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 21, 1-2, 199-205. Scott, B. (2015). “Minds in chains: A sociocybernetic analysis of the Abrahamic faiths”. J. of Sociocybernetics, 13, 1. https://papiro.unizar.es/ojs/index.php/rc51-jos/article/view/983 von Foerster, H., (1993). “Ethics and second order cybernetics”, Psychiatria Danubia, 5, 1-2, pp. 40-46. Wallerstein, I., "Differentiation and reconstruction in the social sciences" Letter from the President, No. 7, ISA Bulletin 73-74, pp. 1-2, October 1997. Wolpert, L. (2006). Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast: The Evolutionary Origins of Belief. Faber and Faber, London.

[i] This paper is an abbreviated, amended and updated version of a paper presented at the 8th International Conference of Sociocybernetics, Ciudad de México, México, July 23-27, 2008, and published as Scott (2009). [ii] In Scott (2015) I use concepts from sociocybernetics to analyse what I see as pathological about the Abrahamic faiths. [iii] The final communiqué of the G7 Conference, Japan, 2016 set ‘global growth as a priority for dealing with threats to the world’s economy and security’. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Being Holistic About Global Issues: Needs And Meanings Dr Bernard Scott Cranfield University Royal Military College of Science Shrivenham Wilts SN6 8LA B.C.E.Scott@rmcs.cranfield.ac.uk Presented at First International Conference on Sociocybernetics, Kolimbari, Crete, June, 1999.Scott, B. (2002). “Being holistic about global issues: needs and meanings”, J. of Sociocybernetics, 3, 1, pp. 21-26. Abstract As sociocyberneticians we are perhaps agreed that the problems we face are global. We may also perhaps agree that our global problems need to be tackled holistically, addressing both the first order complexity of interconnected observed systems and the second order complexities of communities of observers. However, “being holistic” lacks meaning if the implied theoretical ideal lacks a praxis. The question arises, "What is that praxis?" In systemic terms, actualising holism requires a “nucleation”, a centre around which the many facets and levels may cohere and coalesce as “insight” and “intuition”. Where is such a universal “centre” to be found? I argue that it is precisely the perceived need for “centring” that is the “centre” or, rather, may serve as such a centre if we so choose. This position should be acceptable to “postmodern sceptics”, as it allows for an ethically based choice of ontology. It should also be acceptable to those who, by faith, believe in a “beyond our understanding” eternity, in which “goodness, truth and beauty” are one. Thus, as practitioner observers we may hope to move forward in unity of purpose whilst tolerant of our lack of uniformity with respect to “foundational”, “transcendental”, “metaphysical” assumptions. The argument is developed with reference to some key sources in sociology and cybernetics. Introduction “ ….the significance of theory will always remain that a more controlled method of creating ideas can increase the probability of more serviceable results – above all, that it can reduce the probability of creating useless excitement.” Luhmann (1989, Preface, p. xviii). “The self today is for every one a reflexive project – a more or less continuous interrogation of past, present and future.” Giddens (1992). As sociocyberneticians we are perhaps agreed that the problems we face are global. We may also perhaps agree that our global problems need to be tackled holistically, addressing both the first order complexity of interconnected observed systems and the second order complexities of communities of observers. Cybernetics as the science of control and communication (Wiener, 1948) and efficiency of action (Couffignal, 1960) and of circular causality in biological and social systems (von Foerster et al, 1953) invites us to be holistic (Beer, 1967) and transdisciplinary in our thinking (Ashby, 1956). With sociocybernetics (Geyer, 1995), we have an explicit concern with human social systems. The scope and scale of human action on this planet invites us to be global in our concerns. Being holistic As noted, holism implies being transdisciplinary (I use the prefix “trans” to imply both meta and interdisciplinarity). As a cybernetician/systems theorist, one is not “a political scientist”, “an economist” “a social psychologist”, “a sociologist”, “an ecologist” or “a meteorologist” only, one is all of these. Theoretically we may distinguish first and second order concerns. First order cybernetics distinguishes, observes, measures and predicts the behaviour of observed systems. Second order cybernetics adds to that a concern with how observers distinguish themselves and their worlds and how they as, actors, interact in order to bring forth and maintain “forms of life” (Wittgenstein, 1953; Margolis, 1989). The cybernetician accepts explicit reflective recognition that second order cybernetics is reflexive - that he or she is just such an actor and, as such has responsibility for the worlds he or she brings forth . First order methodology explicitly recognises similarities and differences between disciplines – all are concerned, in one way or another, with distinguishing and measuring systems. Second order methodology reminds us that each discipline has brought forth a world, a “universe of discourse”, with metaphysical assumptions, theoretical and methodological paradigms, values and goals. It works to bring practitioners together as reflective practitioners, ready to question disciplinary assumptions (to take risks), to look for new insights and problems to be solved in the “interstices” and “overlaps” of disciplines. We should be proud there are examples of this (cf. several papers presented in the RC51 Montreal symposium, 1998). Methodologies also include the explicitly second order and qualitative approaches of discourse analysis that may reveal (often habitual) relations of power embedded in the form as well as the content of discourse (v. Ahlemeyer, 1997) and associated pathologies of communication in human systems (Scott, 1997). Being global Being global means being concerned for the whole planet – what is happening? What may happen? Epistemologically what does it mean to ask such questions? What answers might we expect? There are two key inter-related issues: (i)sustainable development (largely a set of first order question about system measurement and performance); (ii)maintaining and improving the right of actors to interact – mainly second order concerns with “human rights”, “democracy” and “justice” Many commentators insist (i) is meaningless without (ii). Here I distinguish them for purposes of discussion. For (i) there is a logic that says “We should be humble as part of a larger whole that is unfolding despite our actions”, by, for example, paying attention to Barry Commoner’s “four laws of ecology” (“everything is connected to everything else; everything has to go somewhere; there’s no such thing as a free lunch; nature knows best”). Complex systems may be modelled in a variety of ways. We may “locally” foresee the consequences of negative and positive feedbacks on a particular subsystem’s variables (monetary markets, global warming, population levels, levels of poverty and literacy) but we need to improve and integrate our models so they are more global in scope and do include second order effects of “agents’” actions, as in the economic modelling of Brian Arthur and John Holland, where account is taken of the fact that 98% of all financial transactions are speculations by agents about other agents’ behaviours. For (ii), there is a logic that says “non-democracies” are “social cancers” and that “justice” should be universal and be suitably empowered, together with checks and balances to reduce the risk of the imposition of totalitarian regimes. “The right of actors” to interact implies that access to education and information should be universal – to participate fully members of a society need to be empowered (Pask, 1991). There is a need for the continuous critique of institutions (political, business, educational), a continuous “revolution in the revolution” – not so much to discover new wisdom but perhaps to ensure the light of existing wisdom (Cybernetics and before – Confucius, Buddha, Christ, Marx) is maintained and allowed to bear fruit (Scott, 1999a; Birrer’s paper, this conference). Although I am arguing for a consensus view, there is scope for “agreement to disagree”. I am referring to disagreements about certain “undecideables” (von Foerster, 1993) to do with life, death, time and eternity, good and evil. I argue it is possible for us to tackle global issues holistically, despite such disagreements. Being holistic and global With respect to the need to be both holistic and global, Luhmann (1989) very clearly warns of two dangers: (i)failure to “resonate” with the ecosystem (not being global enough in our concerns); (ii) too much resonance between social systems (not being holistic enough to dampen unfruitful noise and “excitement”). Examples of (i) are many:being parochial with respect to one’s own ecological niche; focussing on one issue (e.g., “global warming” or “poverty”) but not taking cognisance of related issues (e.g., “opportunities for education” or “political freedoms”). Examples of (ii) are also many: the promotion of one scientific discipline over another; the promotion of one political ideology over another. There is then an open invitation for all of us to be less parochial and more global in our concerns and interests. There is a need to listen to other voices, with an honest heart and an open mind. However, holism is called for if we are not to be overwhelmed by noise and excitement. As noted earlier, the phrase “being holistic” refers to the need for transdisciplinary tools and understandings that can facilitate effective interdisciplinary working. There are two problems to be addressed and for which this paper proposes solutions: - “being holistic” lacks meaning for an individual if the implied theoretical ideal lacks a praxis;

- the concept lacks consensual meaning if the praxis is not in some sense one that sociocyberneticians, as actors, may agree to apply together, in concert.

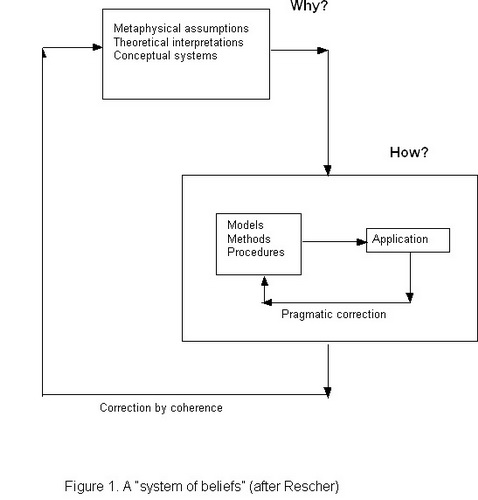

The question arises, "What is that praxis?" (cf. Heidegger, 1978: “Perhaps there is a thinking which is more sober minded than the incessant frenzy of rationalisation and the intoxicating quality of cybernetics....a thinking outside of the rational and the irrational... The task of thinking would then be the surrender of previous thinking to the determination of the matter for thinking”). In systemic terms, actualising holism requires a “nucleation”, a cognitive/affective centre around which the many facets and levels of our concerns may cohere and coalesce as insight and intuition (Capra, 1982), as a pragmatically “true”, coherent conceptual system or system of beliefs (Rescher, 1973, 1977; Scott, 1999b), as an organisationally closed “psychological (p-) individual” (Pask, 1975, 1981) (see figure 1).

Where is such a universal “centre” to be found? I argue that it is precisely the perceived need for a holistic “centring” that is the “centre” or, rather, may serve as such a centre if we so choose. That is, as practitioners it is sufficient to intend to be holistic – and to share that intent - in order for ideas to be created fruitfully. Concluding Comments The theoretical position advanced in this paper should be acceptable to “postmodern sceptics” and “nihilists”, as it allows for an ethically based choice of ontology, without the explicit imposition of a consensual morality (cf. Luhmann, 1989, on the dangers of moral coding and the risk that “all ethical reflections may fail”). It should also be acceptable to those who, by faith, believe in a “beyond our understanding” eternity, in which “goodness, truth and beauty” are one. Thus, as practitioner observers we may hope to move forward in unity of purpose, practising “technologies of the self” (Foucault, 1972; Giddens, 1992) and “cognitive methodologies” (Scott, 1983, 1996), whilst tolerant of our lack of uniformity with respect to “foundational”, “transcendental”, “metaphysical” assumptions. References Ahlemeyer, H. W. (1997). “Observing observations empirically: methodological innovations in applied sociocybernetics”, Kybernetes, 26, 6/7, pp. 641-660. Ashby, W.R., (1956). Introduction to Cybernetics, Wiley, New York. Beer, S. (1967). Decision and Control, Wiley, New York. Birrer, F (1999). “From natural sustainability to social sustainability”, abridged paper for ISA RC51 conference, Kolimbari. Capra, F. (1982). The Turning Point, Wildwood House, London. Couffignal, L. (1960) “Essai d’une definition generale de la Cybernetique”, in Proceedings of the Second Congress of the International Association for Cybernetics, Gauthier-Villars, Namur. Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge, Tavistock, London. Geyer, F. (1995). The Challenge of Sociocybernetics, Kybernetes, 24, 4, pp.6-32. Giddens, A. (1992). Transformation of Intimacy, Polity Press, Cambridge. Heidegger, M. (1978). “The end of philosophy and the task of thinking”. In Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings, D. F. Krell (ed.), Routledge, London. Luhmann, N. (1989). Ecological Communication, Polity Press, Cambridge. Margolis, J. (1989). Texts Without Referents: Reconciling Science and Narrative, Blackwell, Oxford. Pask, G. (1975). Conversation, Cognition and Learning, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1975. Pask, G. (1981). “Organisational closure of potentially conscious systems”. In Autopoiesis. M. Zelany, Ed.: 265-307. Pask, G. (1991). "The right of actors to interact: a fundamental human freedom", in Glanville, R. and de Zeeuw, G. (eds.) Mutual Uses of Cybernetics and Science (Vol 2), Systemica, 8, 1 to 6, Thesis Publishers, Amsterdam. Rescher, N.(1973). Conceptual Idealism, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Rescher, N. (1977). Methodological Pragmatism, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Scott, B. (1983). "Morality and the Cybernetics of moral development", Int. Cyb. Newsletter, 26, 520-530. Scott, B. (1996) “Second order cybernetics as cognitive methodology”, Systems Research 13, 3, pp. 393-406 (contribution to a Festschrift in honour of Heinz von Foerster). Scott, B. (1997). “Inadvertent pathologies of communication in human systems”, Kybernetes, 26, 6/7, pp. 824-836. Scott, B. (1999a). “Forgetting in self-organising systems”, in The Evolution of Complexity, F. Heylighen (ed), Kluwer, Dordrecht (in press). Scott, B. (1999b). “Conceptual coherence and organisational closure”, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (in press). Von Foerster, H., Mead, M., and Teuber, H. L. (1953). Cybernetics: Circular Causal and Feedback Mechanisms in Biological and Social Systems, Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation, New York. Von Foerster , H., (1993). “Ethics and second order cybernetics”, Psychiatria Danubia, 5, 1-2, pp. 40-46. Wiener, N., (1948). Cybernetics, Wiley, New York, 1948 Wittgenstein, L. L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

Up

|