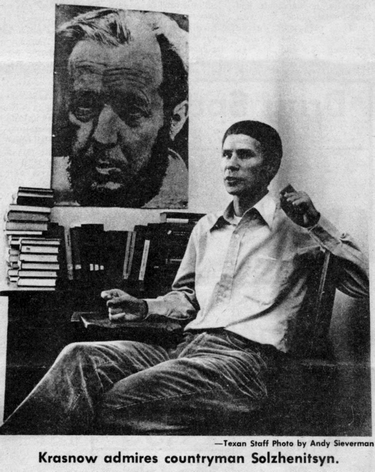

Vladislav Krasnov, personal page: http://peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=752

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Relevance Today Vladislav Krasnov (aka W George Krasnow) ponders on the International

“Reading Solzhenitsyn” Conference in Lyndon, Vermont, September 7-8, 2018

Solzhenitsyn’s Relevance Today Dear friends and colleagues, the topic of my presentation, “If an artist imagines himself as a god…,” alludes to Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Lecture delivered in Stockholm in 1974. There is no better way to celebrate the writer’s approaching Centenary (on December 11, 2018) than by reviewing what he had to say about his art at this festive occasion at half-way of his career. In writing my book “Solzhenitsyn and Dostoevsky: A Study in the Polyphonic Novel”,[3] I was guided by his vision of art, expressed in the Nobel Lecture and elsewhere.

The Nobel Lecture

No, Solzhenitsyn did not imagine himself as a god. He is another kind of artist, the one, he says, who “recognizes above himself a higher power and joyfully works as a humble apprentice under God’s heaven, though graver and more demanding still is his responsibility for all he writes or paints—and for the souls which apprehend it. However, it was not he who created this world, nor does he control it; there can be no doubts about its foundations. It is merely given to the artist to sense more keenly than others the harmony of the world, the beauty and ugliness of man’s role in it—and to vividly communicate this to mankind….”

Those who listened to his Lecture knew very well that he himself had gone through “the lower depths of existence—in poverty, in prison, and in illness” which nonetheless failed to extinguish his “sense of enduring harmony.” They knew that the man in front of them had challenged the mightiest police state in the world. Soviet leaders figured that by kicking him out of the USSR, they will cut him off from his Motherland and deprive his art of its nourishing roots. They miscalculated. Their ruthlessness backfired. Fifteen years later, at the time of perestroika and glasnost, they were mired in a confusion desperately trying to save their System and themselves.

I doubt that by 1991 there were many of them who still believed in the Marxist-Leninist ideology their predecessors had imposed on Russia in 1917 via the October Revolution and bloody Civil War. But in 1974 their professed ideology held sway not just in the USSR but over a third of mankind.

In the Nobel Lecture Solzhenitsyn mentioned neither Marx nor Lenin, but implicitly its main thrust was against both; and against the so called cultural Marxism that dominated Western elites then and is still viral today.

But in 1974 -- how many armored divisions and nuclear missiles silos could Solzhenitsyn marshal against the mightiest military power marching then across the globe under the banner of Marxism-Leninism, the teaching that was thought “all-powerful because it was corrects” (as Soviet propaganda proclaimed)? Solzhenitsyn counted all potential “troops” on his side. “So perhaps the old trinity of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty is not simply the decorous and antiquated formula it seemed to us at the time of our self-confident materialistic youth,” he said alluding to his own training in dialectical materialism as part of Marxist-Leninist indoctrination mandatory for all schools and colleges.

Then he reminded Western elites about the everyday reality of the USSR:“If the tops of these three trees do converge, as thinkers used to claim, and if the all too obvious and the overly straight sprouts of Truth and Goodness have been crushed, cut down, or not permitted to grow, then perhaps the whimsical, unpredictable, and ever surprising shoots of Beauty will force their way through and soar up to that very spot, thereby fulfilling the task of all three”.

The Harvard Commencement Address

On June 8, 1978, Solzhenitsyn delivered the Harvard University Commencement address.The chosen topic was: “A World Split Apart”.He defined it thus: “This deep manifold split bears the danger of manifold disaster for all of us, in accordance with the ancient truth that a kingdom -- in this case, our Earth -- divided against itself cannot stand”. This split was caused by the Cold War between the USSR, PRC and their allies who espoused the need for a violent world revolution and the rest of the world that remained unsure whether Marxist “doctors” practicing vivisection offered the right cure. Soviet professions of “peaceful co-existence” abroad sounded hollow when Soviet leaders refused to “peacefully co-exist” with their own citizens.

Then Solzhenitsyn focused on the West’s failure to understand Russian civilization’s dire predicament under Soviet ideological rule. According to him, “Western thinking systematically committed the mistake of denying its (Russia’s) autonomous character and therefore never understood it, just as today the West does not understand Russia in Communist captivity.”

Some of his predictions sound even more prophetic today: “if our society were to be transformed into yours, it would mean an improvement in certain aspects, but also a change for the worse on some particularly significant scores”, such as “those offered by today's mass living habits, introduced by the revolting invasion of publicity, by TV stupor, and by intolerable music.”

To be sure, some Americans were disappointed by the seeming lack of praise for the USA. But then Solzhenitsyn’s purpose was not to flatter the country that gave him refuge but help it lead the world in resistance to Communist violence.

James Herold, a prominent New England architect and our Forum’s participant, was in the Harvard crowd of some twenty thousand who came to listen to the Russian in driving rain. He remembers he heard people saying: “Who is this guy who teaches us how to live!” But James felt “this guy” was right about America then and even more now.

One Day

It all started on one day in November 1962 when Solzhenitsyn’s first tale, “One Day of Ivan Denisovich,” was published in Novyi Mir, a leading Soviet magazine, after the party boss Nikita Khrushchev gave the permission. The story of its publication was indeed as “whimsical, unpredictable, and surprising” as was its great appeal to Soviet readers. It bordered on the miraculous. It was then that the USSR began a decisive slide from “Soviet” to “Russian”, from Marxist “materialism,” “class struggle” and “world revolution” to such idealist notions as Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. This slide toward Russian spiritual identity was sometimes brutally interrupted but never stopped until the collapse of USSR in 1991.

As it turned out, Solzhenitsyn’s writing was deeply grounded in Russia’s soil. “And then no slip of the tongue but a prophecy would be contained in Dostoyevsky’s words: “Beauty will save the world.” For it was given to him to see many things; he had astonishing flashes of insight,” the writer said in Stockholm.

Dostoevsky proscribed

The few roots of Russianness surviving in the USSR by the 1960s had been trampled upon, ignored and abused—in favor of Marxism, a Western chimera, imposed on Russia. For many years Dostoevsky himself was excluded from Soviet school programs as a “conservative counter-revolutionary” and – Marx Forbid! – Christian “fanatic” peddling the “opium to the people”. And he was not the only Russian classic ignored and abused in the USSR. In the GULAG Solzhenitsyn met a number of followers of Lev Tolstoy’s non-violence. Ever since Lenin wrote that in Tsarist Russia

TWO CULTURES were in a mortal combat, the one of “progressive revolutionary and democratic” Westernizers, and the other of “reactionary conservative” land-owners and Slavophiles, Soviet censors knew where to apply their scissors.

In addition to the “Slavophiles,” they removed from school-rooms, libraries and even archives, all deviant authors, including those of proletarian origin, if they failed to follow the “party-line” (Wonder where does the current “political correctness” come from?).

They certainly removed from book shelves the works of over 200 non-revolutionary Russian philosophers (Nikolai Berdyaev, Sergei Bulgakov, Semyon Frank, Ivan Ilyin, Abram Kagan, Pitirim Sorokin etc.), thinkers, and scholars whom Lenin ordered shipped to the West in 1922. The fate was no kinder to millions of “White Russians” who had to flee Russia for life. Inevitably, some “Old Regime” scholars stayed on and even tried to absorb the “scientific wisdom” of Marxism out of curiosity or just to survive.

Mikhail Bakhtin denounces the monological principle

One of them was Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975), a literary scholar educated in old “tsarist” Russia. In 1929, after exposing himself to certain Marxist tenets, he published a book in honor of the officially disapproved Dostoevsky. He praised the novelist for his ability to hear a whole POLYPHONY of diverse ideological voices and stay fair even to those with whom he disagreed. Prompted by Solzhenitsyn’s 1967 interview with Pavel Licko in which the writer declared his allegiance to a polyphonic approach in his novels, I began to explore Bakhtin for my Ph.D. thesis at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Soon I learned that, after being exiled for several years to Central Asia, Bakhtin, just like Solzhenitsyn, was rehabilitated. However, finding a teaching position at a provincial university, he did not renounce his scholarly thesis but – 34 years later! - came up with a new expanded edition of his book. Now Bakhtin boldly asserted that Dostoevsky’s polyphony was not an isolated matter of novelistic style, but “concerns prime principles of European aesthetics.”

In fact, he called Dostoevsky the creator of “new artistic model of the world” in opposition to “the monologic principle as the trademark of modern times.” Bakhtin asserted that “In modern times, European rationalism with its cult of unified and solitary reason, and particularly the Enlightenment, during which the basic genres of European prose were formed, contributed to the strengthening of the monologic principle and its penetration into all spheres of ideological life.”

Bakhtin clearly alluded to the official Marxist ideology when he said that “All European utopianism is also founded on this monologic principle. And so is Utopian socialism with its belief in the omnipotence of persuasion.” one could add that the latter belief had to be re-enforced by the GULAG and other corrective tools that came to the fore when persuasion failed. That’s what I said in my Ph.D. dissertation which in 1979 was published as a book, Solzhenitsyn and Dostoevsky: A Study in the Polyphonic Novel.

“Russian literature vs. Marxist maculature”

Now we come to the alternative title of my presentation: “Russian literature vs. Marxist maculature”. I first used this juxtaposition in my next book “Russia Beyond Communism: A Chronicle of National Rebirth” published in the USA just before the fall of the USSR. This juxtaposition had a double entendre. First, it alluded to Marshall McLuhan’s notion that the medium is the message. Marx’s teaching was touted as a “science” of economics which dictated the need for a violent world revolution to conform to allegedly objective law of social development. Thus, the appeal was seemingly to reason.

Russian literature, on the other hand, like any other literature, only more so, appealed to the heart and soul of the reader, that is to the whole, holistic, human being. It appealed to his ethical and esthetic sense, indeed to Truth, Goodness and Beauty. To be sure, it also appealed to his rational mind and imagination, the latter being an important source of scientific discoveries, as Albert Einstein testifies. Such holistic view of life has animated Russian literature. That view of life may appear less “rational,” “clever,” and more “idealist” than Marxism, but it is still much wiser because it is true to life.

Second, the “maculature” (makulatura in Russian) alludes to an overload of Soviet propaganda materials, especially the works of Marxist-Leninist “classics” (Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin), which Soviet readers simply could no longer absorb. So they turned them into a second-use, blotted paper – makulatura in Russian - to be dumped in garbage cans. However, in the waning years of the USSR, there were organized campaigns to collect the unused works of the “classics.” They were sorted out by weight in kilograms and exchanged for a volume or two of “old-fashioned” Russian or foreign classics.

The point here is not to denigrate Marx’s economic theory or the “law of added value”. The main issue is an excessive, almost demonic obsession of Marx that he had discovered a fail-proof key to the happiness of mankind, if only the proletariat would obey the iron-clad “scientific” laws of history that dictate violent world revolution.

Dostoevsky, Bakhtin and Solzhenitsyn were familiar with both sides of the issue. Dostoevsky faced an execution squad for his sympathy for the “poor and downtrodden” and for his alleged participation in revolutionary circles. Bakhtin was active in Marxist study groups. Solzhenitsyn, during his university years regarded himself a Marxist and Communist. But all three, like thousands of their readers, came to the conclusion that the world revolution, after shedding rivers of blood, sweat and tears, failed to get rid of exploitation and injustice – and then covered up its failure by mandatory falsehoods.

Yevgeny Zamyatin, the first dystopia

One of the first Russian writers to notice that the October 1917 Bolshevik revolution went astray was Yevgeny Zamiatin (1884-1937), whom Solzhenitsyn mentioned in his Nobel Lecture as an example of Russian visionaries. Zamyatin was a prominent author before 1917 and was also active in, and imprisoned for, Bolshevik revolutionary activities. This did not prevent him from writing in1920 the novel “WE,” a vision of a sterile and inhumane totalitarian society where all individual life was suppressed. Published in Germany in 1921, “WE” became the first dystopian novel in history of Europe. Soon it was followed by such Western classics as Aldous Huxley, Brave New World; Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon, and George Orwell’s Animal farm and Nineteen Eighty Four. Zamyatin’s novel was banned in the USSR and he barely succeeded in leaving the country.

Were Zamyarin’s novel timely published in Soviet Russia, would it not have saved millions lives in Russia allowing it evolve as a normal country where heterodoxy is tolerated? Would not the whole the 20th century have been less bloody?

Zamyatin’s favorite notion in the novel “WE” was entropy as a measure of energy that is needlessly dispersed in any given endeavor. It appears that mankind learned nothing from the bitter fate of the “rationalist” French Revolution which degenerated into revolutionary self-terror and Napoleonic wars of conquest. Alas, Lenin enjoyed his Bolsheviks to follow the French extremists, just do it “more decisively”.The entropy of the Bolshevik dystopia in Russia was countless times higher.

Let me say a few words about my essays that Solzhenitsyn liked. one was on Marx’s poetry debut. Two others are about the role of national character in a country’s history.

Karl Marx as a romantic poet

After I chose a voluntary exile from the USSR in 1962, I tried to read as much as I could the authors who were suppressed. But what I discovered was that censored were not just the works of anti-Communists, but even “classics” of Marxism-Leninism, including Marx himself. Certainly, his Jewish origin was barely mentioned and deemed irrelevant. His article “On the Jewish question” was not known at all. Then I discovered that at youth he was an ardent Christian, more so than his newly converted parents. Later, he came to see himself as a romantic poet. That’s what Oulanem, the young Karl’s romantic hero and alter ego, proudly proclaims in his poem of the same name: The world which bulks between me and the Abyss I will smash to pieces with my enduring curses! I will throw my arms around its harsh reality. Embracing me, the world will dumbly pass away And then sink down to utter nothingness. Perished, with no existence - that would be really living.

As you now see, in terms of my presentation, it was Marx, not Solzhenitsyn, who imagined himself as a god, not just in youth, but also when he wrote “Manifesto of the Communist Party”.

Karl Marx as Dr. Frankenstein

I quoted these lines in my 1977 essay “Karl Marx as Frankenstein: Toward a Genealogy of Communism”. It was based on Mary Shelly’s 1818 horror story “Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus”. My intentions was not to put the young Marx down but rather to investigate how a prima facie Romantic poet transforms himself to a modern Promethean economist and ruthless political leader ready to endow the oppressed proletarians with the “gift” of world revolution fire.

The most intriguing aspect of Shelly’s work was that she let the well-meaning German scientist, Dr. Victor Frankenstein, create an artificial human being. Successfully! To be sure, Shelly’s artistic vision was spurred by the rapid advancement of science in Europe. However, as soon after the talented Victor celebrated his scientific victory, his creature started to misbehave turning doctor’s scientific Victory into a crushing defeat. His creature became The Monster so lavishly serialized in numerous Hollywood productions.

To be fair to Miss Shelly, she portrayed Frankenstein as a responsible man who tried to restrain his Creature. That failing, he tried to remove the Monster from densely populated centers of Europe. But where to? He found no better place than “the wilderness of Russia and Tataria” as it was known in Europe since Napoleon’s attempt to conquer it.

Russia as a Dumping ground for Western “science”

Something similar happened to Marx’s “creature”. He designed his world revolution for the most advanced countries, but no country in Europe wanted to serve as a lab. Finally, in 1917, a small group of international Bolsheviks of various ethnic backgrounds forced Russia to volunteer, in spite of the fact that the proletariat there was a small minority. Whether by a conspiracy or bad luck, Russia became the first lab for the Marxist experiment in building what was paraded as the first ever equitable and happy society since the Noah’s Ark. Thus Russia took upon itself the “Promethean”, God-fighting, theomachic, or Luciferan, if you will, task of re-making the world in defiance of any hitherto established religions, be it Christian, Judaic, Moslem or whatever.

I wrote this essay in 1976-1977, when the United States were swamped with thousands of Jewish immigrants fleeing from the USSR after a special deal between Brezhnev and Kissinger was made to allow Soviet Jews to emigrate “for family re-unification.” I saw this as a further irony of the Marxist dystopia transplanted in Russia. Because of his own Jewish background, was it not likely that Marx himself, had he lived in the country of his dream, would seek an exit visa? To Israel? Or the United States? In any case, Mary Shelly’s 1818 horror fiction turned into reality exactly one-hundred years later.

Max Weber undermines Karl Marx

Two other essays that Solzhenitsyn liked dealt with the role of national character in history. Of course, since I was trained as ethnologist and anthropologist in the USSR, I knew that any attention to national character was pretty much under a taboo lest it undermines the international solidarity of working people. But as soon as I defected, I hurried to read the forbidden books, including Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism . I readily agreed with much what he had to say. Indeed, national character fostered as it has been by a belief system (religion, customs, habits, geography, history etc.) of a nation had considerable bearing on its economic standing in the world. It certainly had more influence on the disparity of income levels of different groups of population than the Marxist notion of exploitation of all working people.

Even though Weber’s thesis seemed to favor Protestant nations, he did not imply any racial or religious favoritism. He was good enough to point out, for instance, that Russian Christian Old Believers on the eve of Revolution had considerably better working habits than the rest of the population. Ironically, this was due to the thrift and communal spirit they had fostered thru centuries of official persecution. As it happens, the majority of most successful Russian entrepreneurs – and arts benefactors - before 1917 were from the families of Old Believers. Had the Russians read Weber’s works on a scale of one to a thousand Marxist makulatura volumes, would they not have been better prepared to the challenges of neoliberal economics imposed on them since 1991?

Whose fault: The Russian Mind or Western Cultural Marxism?

Soon I challenged Ronald Hingley (1920 – 2010), a prominent British historian and specialist on Russia, for suggesting in his book, The Russian Mind that Communist Totalitarianism was due to the disorderly national character of ethnic Russians whom he had observed both in the USSR and among Russian immigrants in UK. Rather than objecting to his observations, I argued that the expansion of Totalitarian rule in Europe and elsewhere was mostly due to the defeatist state of mind of Western intellectual and media establishment who were either tacitly or openly pro-Marxist. They protected their Idol by blaming the brutishness of Communist takeovers on innate boorishness of ethnic Russian apparatchiks rather than the inherent inhumanity of Marxist ideology they followed. Did Marx not enjoined his followers to reject all existing morality, especially Christian, as rooted in “bourgeois” mentality?

Richard Pipes’s Russophobia

One of Marx’s protectors was Harvard professor of Russian history Richard Pipes (1923 – 2018). He had the reputation of anti-Communist hard-liner, but argued that Soviet leaders cannot be trusted not due to their different ideological precepts but because they were usually descendants of Russian peasants who were cheats because their ancestors were serves who could survive only by cheating. It was an ethnic slur, I thought, and challenged him in my article “Richard Pipes's Foreign Strategy: Anti-Soviet or Anti-Russian?”

In case the link fails to download, here is its summary in my 1991 book “Russia Beyond Communism”. “A respectable historian, (Pipes) has exerted considerable influence on U. S. foreign since he was National Security adviser in the Reagan White House.He has also been one of the chief purveyors on an essentially russophobic conception of Russian history... he blames, for instance, the brutality of Soviet regime chiefly on Russian national character as embodied in Russian peasants. Pipes is an avowed Solzhenitsyn opponent. Not only did he allege that the writer was “anti-Semitic” but ruled out any positive role for Solzhenitsyn in Russian future” (p. 281).

Earlier, on November 13, 1985, in a paper I read at the World Congress for Soviet and East European Studies in Washington, DC, I publicly defended Solzhenitsyn from the charges of “anti-Semitism” coming from Pipes and his ilk. This was duly reported by The New York Times. As the reporter Richard Grenier noted, I was not alone. “Prof. Adam Ulam of Harvard, another Soviet specialist, said Professor Pipes's characterization of Mr. Solzhenitsyn was ''very unfair.'' Grenier went on: “Conquest, author of ''The Great Terror,'' called the charge of anti-Semitism ''ludicrous.''

Grenier also pointed out that Solzhenitsyn got support also from a number of prominent people, including Jews, from the USSR and abroad: Mstislav Rostropovich, Mikhail Agursky (Soviet dissident, then professor at Hebrew Universty) and Elie Wiesel. Finally, Grenier said, “Willing to go further in his defense than Mr. Solzhenitsyn himself was his wife, Natalia, who is herself half-Jewish. The charge of anti-Semitism is ''nonsensical'' and ''absolutely absurd,'' Mrs. Solzhenitsyn wrote in a letter. Her husband was surrounded by Jewish friends in Russia, she said, both in and out of the Gulag”.

In 1989 I was able to arrange for an interview with Solzhenitsyn by David Aikman for Time magazine. David was my friend and colleague in the Department of Slavic and Far Eastern Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. The interview was introduced by the publisher: "One Word of Truth: A Portrait of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn… a courageous man devoted to the battle for truth in the context of the distinctive disorders of modern, post-Christian culture”.

Polyphony in the Period of Glasnost (1986-1991)

At about 1986 when I set out to write a book about Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, I decided to apply polyphonic principle in my selection of dozens Soviet and expatriate “voices of glasnost” of various political and ideological leanings. All of them argued that the USSR had no Communist future and therefore Russia, as well as other ethnic entities of the Soviet Union, have to go back to their past in order to find an inspiration for their future. In short, I made my selection in favor of authors who were not destined to Marxist makulatura dust bins. In 1991, when the USSR was still intact, my study was published as a book, “Russia Beyond Communism: A Chronicle of National Rebirth.”

As a prototype for reforms I suggested Solzhenitsyn’s “Letter to the Soviet Leaders” (1973). It offered a program of gradual “Russification” of the USSR. No, Solzhenitsyn did not ask Soviet leaders to relinquish their hold on centralized state power. He only insisted on allowing patriotic ethnic Russian non-party members of Christian persuasion into the ranks of country leadership. As to the official ideology of Marxism-Leninism, Solzhenitsyn advice was: “give it away to the Chinese.” At that time Mao-Tse-Tung accused Moscow of “revisionism” and declared himself the true bearer of the flag of Communism. I was delighted to see two scholars from the People’s Republic of China participating in this forum. They assured us that Solzhenitsyn, totally unknown there during the 1960-s and 1970-s, has lately been on the rise and his books are sold in millions of copies.

At any rate, the PRC leaders woke up sooner than those of the USSR. They became less dogmatic after the devastating Cultural Revolution. Even without reading Solzhenitsyn, they intuitively followed some of his suggestions to Soviet leaders. Under Deng Xiaoping (1904 – 1997) they began to lean back on China’s cultural heritage and abandoned a number of Marxist dogmas by adapting a more pragmatic approach to China’s economy.

Soviet leaders, on the other hand, were too slow in shedding Marxist dogmas, certainly, in running their moribund economy. Remarkably, Solzhenitsyn mailed his Letter to all Soviet party bosses. None replied to the Nobel Prize winner in dereliction of their duty toward their citizens.

The Letter was quickly published in English. Alas, the reception in the West was rather hostile. It was judged as a quirk of an old man who allegedly turned to Russian “chauvinism” and “Tsarist past” while failing to see the bright future of a country successfully competing with the USA in space exploration. None noticed that Solzhenitsyn sought a gradual and peaceful evolution of Soviet society, even the possibility for the border republics to secede if they wished, via referenda.

“Why Not Solzhenitsyn?” A letter to Mikhail Gorbachev

In spite of the negative reception by US academic establishment, Solzhenitsyn’s world fame continued to grow. During the waning years of Gorbachev’s perestroika when the Berlin Wall already fell and Poland and Czechoslovakia gained independence, I was feverishly working on my book “Russia Beyond Communism.” Still, I managed to urgently write the column “Why Not Solzhenitsyn?” on February 10, 1990, it was carried by “The San Diego Union”, a major California newspaper.

“As the events in Eastern Europe have shown, people are now looking for a new breed of leaders, such as Solidarity founder Lech Walesa and Czech dissident playwright Vaclav Havel ”, I stated. “As for the Soviet Union, no one is better qualified for a national leader than Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the Nobel Prize winning novelist…After the untimely death of Andrei Sakharov, a nuclear scientist and a fellow dissident Nobel Peace prize winner, none come even close to the high moral ground Solzhenitsyn so eminently occupies.”

As soon as the article was published, I sent a copy to Solzhenitsyn with whom I had been corresponding for a number of years. Then I wrote an Open Letter to Mikhail Gorbachev asking him to consider the implications of my article (a copy of which was inserted in the envelope). I asked Gorbachev to officially invite the world-famous author to return to Russia. A copy of my letter to Gorbachev, as well as of my article, I mailed to a number of Soviet newspapers.

Alas, I received neither reply nor even an acknowledgement from the Kremlin. This is hardly surprising since the relentless Gorbymania of Western media made Gorbachev confident of the one-party rule. Nor did I get any reply from Soviet media moguls, except one small Young Communist League’s newspaper in my native town in Perm that carried my Open Letter to Gorbachev.

I was disappointed but not too surprised. I knew of both lethargy of Soviet nomenklatura members[32] and the

slowness and unreliability of Soviet postal clerks, especially, with overseas mail.

Still, I felt more disheartened by a rather angry letter from Solzhenitsyn himself. He sternly reproached me for “dragging me into Russian politics without asking my permission.” I replied that I did not have to ask for permission for suggesting a course of action for my Russian compatriots to facilitate a peaceful transition to a post-Communist Russia. While the thrust of my Letter was on securing a timely and honorable return of Solzhenitsyn to his homeland, I left it up to Soviet authorities and public to devise their own ways of using Solzhenitsyn’s world fame and talents which were certainly not below those of Walesa and Havel.

How Can We Make Russia Livable

Still, a few months later I learned that my effort was not entirely wasted. Apparently my letter to Gorbachev prompted Solzhenitsyn to finally speak up about what needs to be done to take the USSR out of the dead-end of Communism. Here is what I wrote then in my book “Russia Beyond Communism: A Chronicle of National Rebirth” that just appeared in 1991:

“A portentous event took place in Moscow on September 18, 1990. The Communist Youth League’s newspaper, Komsomol’skaia Pravda, brought to its nearly 22 million readers the long-awaited word of Solzhenitsyn, his pamphlet, ‘How Can We Make Russia Livable [Kak nam obustroit’ Rossiiu]’. The following day the weekly Literaturnaia gazeta offered the same to an additional 4.5 million readers. The event was extraordinary by any standard. only five years earier these newspapers had berated the exiles author as ‘that vile scum of a traitor’” (p. 43)

Here is not the place to discuss Solzhenitsyn’s pamphlet in detail. So I repeat its brief assessment in the book: “Solzhenitsyn’s central idea is that the particular form of government and economy is secondary to a nation’s spiritual foundations. ‘If the spiritual resources of a nation have dried up’, he says, ‘then not even the best form of government, nor any sort of industrial development, can save it from death.’ one of the chief sources of the present malady is precisely the fact that the Communists reversed the order of priority by putting the ‘cart’ of economic and political power before the ‘horse’ of spirituality of human relations. As a result, not only the country’s political institutions, economy, and ecology but also ‘the souls’ of the people were destroyed in the name of the Marxist Utopia” (p. 53).

I was unable to judge the situation in the USSR during the few crucial months after the publication of Solzhenitsyn’s pamphlet as I was not rehabilitated yet from the same charges as were leveled against Solzhenitsyn. only in April 1991 was able to set my foot in my home country for the first time after twenty-nine years of voluntary exile. My subsequent visits to Russia during the 1990s were short and intermittent.

Aleksandr Sevastianov: Solzhenitsyn was late

So much more I was delighted to read the following lines of Aleksandr Sevastianov, a self-avowed Russian nationalist and perceptive observer of Russian politics. In a 2009 article dedicated to Solzhenitsyn’s memory he wrote: “The timely arrival of Solzhenitsyn could have instantly changed the balance of power, give an absolute advantage to the patriotic wing of dissidence, shorten the hands of traitors, robbers and fraudsters, haters of Russia. No one had a greater prestige at that moment — not even Yeltsin. He himself live was then much more necessary in Russia than his books. His opponents were afraid of his arrival; they did everything to prevent his contacts with Yeltsin! For it could be otherwise”.

Sevastianov also reported that “the Prosecutor General announced the termination of the case (against Solzhenitsyn) under article 64 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR (treason) in the absence of corpus delicti. The last obstacle for his return fell. Friends and admirers even those beyond the Iron Curtain, chant: "You are needed at home." This is the truth. But Solzhenitsyn failed to return to Russia. To me, it is an inexplicable”.

“Again a unique opportunity was missed,” morns Sevastianov, and then quotes Solzhenitsyn’s lame excuse: “So what - I did return at the moment of the highest political expectations of me in my homeland. And I am sure that I was not mistaken then. It was the decision of the writer, not a politician. I never groped for political popularity for even a minute. ”

Sevastianov disagrees it was a political issue. It was a call of history that Solzhenitsyn failed to respond to. I tend to agree with Sevastianov. But, being like him a great admirer of Solzhenitsyn, I am just as reluctant to blame exclusively the writer. If anything, the Russian intellectuals of the early 1990s, even the dissidents among it, were not as mature as those in Poland and Czechoslovakia to answer the history call. After all, they had stayed under totalitarian foot a whole generation longer. So I see it rather as a judgment from the Above--for the sins of October Revolution. The country had to be meted out an additional punishment in the form of lawlessness and oligarchy misrule during the 1990s.

Egor Kholmogorov

Another Russian admirer of Solzhenitsyn, Egor Kholmogorov, in a recent article translated for The Unz Review as “Alexander Solzhenitsyn - A Russian Prophet” also thinks that the writer may have missed a chance to set Russia aright during 1991-1993. Like Sevastianov he gives very high marks to Solzhenitsyn’s statecraft proposals contained in the pamphlet: “Some formulas coined by the writer became part of government policy, such as the emphasis on the “preservation of the people”. Others became a political reality, such as his call for a nationally minded authoritarianism, as opposed to the aping Western multiparty democracy. There are also still many – such as his ideas regarding the zemstvo, organs of “small-space democracy” – that are yet to be widely heard and discussed”.

Moreover, Kholmogorov throws a gantlet to the West by praising Solzhenitsyn for “putting forward a detailed and consistent anti-Enlightenment doctrine: A return to God, voluntary self-restraint and self-restriction of humankind, emphasizing duties instead of ever-expanding “rights”, prioritizing inner freedom, and rejecting the sacrifice of national life not only to totalitarian utopia but also to the orgy of freedom. Solzhenitsyn’s doctrine is one of the most consistent and politically sound Conservative philosophies formulated over the last couple of centuries. His duel with the ghosts of Voltaire and Rousseau goes on after his death, and the score is still in the Russian writer’s favor.”

Lest one suspect that Solzhenitsyn’s Russian admirers naturally tend to exaggerate the importance of their countryman in world history, in my view, spiritually attuned readers outside of the USSR, especially those with Christian roots, have been just as fascinated with him as a cultural hero and world historical phenomenon. I mentioned some of them in my book “Solzhenitsyn and Dostoevsky”. Thus, Heinrich Böll (1917 –1985) , one of Germany's foremost writers and Nobel Prize winner himself, felt that there was a metaphysical level in Solzhenitsyn that was simply inaccessible for Western writers.

As professor of Russian Studies, language and literature, I observed a salutary impact of Solzhenitsyn on my students. During the turbulent Vietnam War era, more than once, I heard that Solzhenitsyn saved them from getting involved in insurrection against the status quo in the US. The tragic experience of Russia in the wake of October Revolution certainly cooled off many hot heads in the USA.

Eldridge Cleaver

One such hot head was Eldridge Cleaver whose book “Soul on Ice” was the rage around the States, especially on campus of the University of Washington in Seattle where I taught as a teaching assistant to provide for my Ph.D. studies. During the 1980s, I started corresponding with this former leader of the Black Panther Party, arguing that in some respects American Blacks were “freer” than “white” Russian dissidents inside the totalitarian police state. Later, I met him at a social event at the Hoover Institution. He was there with his wife Kathleen. By that time I knew that, after travelling to Cuba, Algeria and some communist countries Eldridge came to the conclusion that the plight of Blacks in the USA was not as bad as usually reported. I wandered what caused him to change his mind besides the travels; he beckoned to Kathleen and said: “She started to read Solzhenitsyn and then made me do the same. After the reading, we never were the same”.

It is obvious that Westerners of Christian cultural background have been more than others keen on Solzhenitsyn. A number of my articles, including on Solzhenitsyn, were published by a Conservative Catholic magazine Modern Age. Some others were carried by a Methodist review affiliated with the Southern Methodist University where I taught from 1974 to 1977.

Professor Edward Ericson

Shortly thereafter professor Edward Ericson, the author of “Solzhenitsyn, the Moral Vision,”[40] invited me to speak

on at Calvin College campus. We became fast friends. I thought of his excellent 1980 book as soon as I got Professor

Alexandre Strokanov’s invitation to the Solzhenitsyn Forum at the Northern Vermont University. I immediately wanted to forward it to Ericson. Sadly, I missed him as he passed away in April 2017.

There is no better way to honor the memory of Professor Ericson than by quoting from of a review of his book written by Bradley P. Hayton. Titled “Americans Need Morally Corrective Glasses,” it says: “Whether or not we have ever chanced a reading, the writings and speeches of Solzhenitsyn have made great impacts on all our lives. Evangelicals, left wing as well as right wing, have been powerfully reaffirmed in their contentions that morality is at the base of all society. Solzhenitsyn is a man with a moral vision, a vision that sees the absolute and direct connection between morality and art, morality and literature, morality and politics”.

Hayton’s review fully confirms Kholmogorov’s contention that Solzhenitsyn is a world phenomenon. He focuses on the most salient trait of Solzhenitsyn’s mission to the world:

“Solzhenitsyn is not theoretical. His writings are grounded in reality, in life, and in action. He is a Christ-like figure, fully human and yet with a divine mission and moral vision. He feels the pangs of human suffering, knows human sin, and heralds human salvation. He has been likened to a prophet who proclaims words of encouragement and hope to a people in despair and darkness. He stirs our minds to the realities of ultimate concern in the face of death”.

Robert Legvold on Daniel Mahoney’s book

Of later books about the writer I would recommend Aleksandr Daniel Mahoney’s Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: The Ascent from Ideology.The title spells out its thesis: secular ideologies which plagued the 20th century offer no salvation for global politics.

Robert Legvold, a knowledgeable and perceptive specialist on Russia and global politics, reviewed the book for “Foreign Affairs”. He says outright: “Mahoney reintroduces Solzhenitsyn as a political thinker who deserves to be included in the ranks of Raymond Aron, Jacques Maritain, Martin Buber, and John Dewey, among others.”

“Trying to free Solzhenitsyn from the reactionary and antediluvian reputation he has in the West”, Legvold rightly observes, “Mahoney highlights his deeper commitment to government under the rule of law and the right of "every private citizen" to "independence and space”…Above all, he would vanquish ideology, that most pernicious product of the Enlightenment, with its arrogant and limitless inhumanity justified in the name of "Historical Necessity." It seems that both Mahoney and Legvold are in agreement with Sevastianov and Kholmogorov on the pernicious role Marxist ideology played in Russia’s history, as well as of its corruptive influence in the West, especially when paraded as “Cultural Marxism”.

The Tour of Solzhenitsyn’s Estate

After two full days of conferencing at Northern Vermont University in Lyndon, we were very fortunate to have made a trip to Cavendish where we saw the house of Solzhenitsyn as well as the Museum of Local History. Mr. Ignat Solzhenitsyn, the writer’s son and a prominent musician himself, gave an excellent tour of his father’s writing and research quarters. He made it clear that the whole family was happily involved in the writer’s titanic effort to free Russian history from Soviet distortions and omissions. All family worked 12 hours every day. Happily? Yes! Ignat says that the house routine also included one and a half hour every day when father directly interacted with his three sons teaching them physics and math.

Margo Caulfield: “The Writer Who Changed History”

Our visit to the Museum of Cavendish was revealing. In addition to its local history, a major part of the Museum was dedicated to the memory of its most famous exile. In addition to seeing many Solzhenitsyn photographs decorating it walls, we had a chance to talk to Margo Caulfield, the Museum’s supervisor and Director of Cavendish Historical Society.

I immediately saw on her desk a book with the remarkable title: “The Writer Who Changed History”. As it turned out, the book’s author was Margo Caulfield herself. on its back cover, I read “This book was born of an attempt to answer an American third-grader’s question: “How could it be that a decorated Soviet officer was removed from the front lines and imprisoned for years simply for making a negative comment about Stalin?”

It was a good question, and Margo Caulfield answered it superbly in her children’s book “Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn:The Writer Who Changed History”. Well documented and illustrated, it is brief but comprehensive. Above all, it is written in the awareness that America needs to grow to the stature of a man to whom it gave a refuge and freedom to restore 20th century history, at least, as far as Russia is concerned.I read the book when I was flying from Vermont to Moscow. I kept thinking that Russian youngsters too need to read such books to fortify their resolve to make the 21st century less cruel and more promising than the Brave 20th Century World.

It is not for nothing that Hilton Kramer of The New York Times once called Cavendish “the capital of contemporary Russian literature”.

The Ark of the First Circle

As a matter of fact, just last night my dear friend and I watched the last sequel of the film series based on Solzhenitsyn’s novel “The First Circle” for which he got the Nobel Prize. The film for which Solzhenitsyn was the screen writer was shown on Russian television channel “Kultura” in the course of a week. We were overwhelmed by the fact that the prisoners of a research lab involved in Soviet armaments program were actually condemned to the “easy” first circle of the Dantean Hell. “Easy” - because they were better fed and able to question the system unlike prisoners of the deeper layers of the GULAG or even the “free” citizens outside the barbed wires who lived in a constant fear of making a political mistake.

Toward the end of the show Solzhenitsyn’s own voice behind the screen (the film was made in 2006 when the writer was still alive) reminded the viewer of what was the highest point of the novel. Reviewing the chapter titled the Ark and placed near the middle of the novel, Solzhenitsyn says that the sleeping quarters of the prisoners were placed in the middle of a half-destroyed Russian church near its cupola. The inmates had just celebrated the birthday of one of them, and prepared for the night. Solzhenitsyn’s voice says:

“From here, from the Ark, confidently plowing its way through the darkness, the whole tortuous flow of accursed History could easily be surveyed as from an enormous height, and yet at the same time one could see every pebble on the river bed, as if one were immersed in the stream. In these Sunday evening hours solid matter and flesh no longer reminded people of their earthy existence. The spirit of male friendship and philosophy filled the sail-like arches overhead.

Perhaps this was, indeed, that bliss which all the philosophers of antiquity tried in vain to define and to teach others.”

It is hard to disagree with Hayton who sees Solzhenitsyn as “a prophet who proclaims words of encouragement and hope to a people in despair and darkness”.

Hayton praises Ericson for showing Solzhenitsyn “as a man driven by a moral vision. He penetrates into the many writings of Solzhenitsyn, unleashing his Christian view of life that envelopes every sphere of human activity. In order to demonstrate the remarkable continuity in the vision of Solzhenitsyn, Ericson freely quotes from the author throughout. Solzhenitsyn's powerful message grips the reader on every page as Ericson probes into each of his writings and speeches.”

George Friedman

It would be wrong, however, to think that Solzhenitsyn’s appeal is limited to conservatives and Christians. No, his appeal extends to people of all nationalities and walks of life. George Friedman was born a Hungarian Jew whose parents survived the Holocaust and then escaped from Communist Hungary. He is the former founder of STRATFOR, a private intelligence firm, and now runs Geopolitical Futures. That’s what Friedman wrote in his Obituary article “Solzhenitsyn: Struggle for Russia’s Soul” on September 7, 2008:

“There are many people who write history. There are very few who make history through their writings. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who died at the age of 89, was one of them. In many ways, Solzhenitsyn laid the intellectual foundations for the fall of Soviet communism. That is well known. But Solzhenitsyn also laid the intellectual foundation for the Russia that is now emerging. That is less well known, and in some ways more important”. Friedman is certainly right when he says that “Solzhenitsyn was far more prophetic about the future of the Soviet Union than almost all of the Ph.D.s in Russian studies. Entertain the possibility that the rest of Solzhenitsyn’s vision will come to pass. It is an idea that ought to cause the world to be very thoughtful”.

“Thoughtful”, sounds just right. But I would go further. If we are really thoughtful, we may see that Solzhenitsyn has had and is likely to have more healing effect on the West in general and the USA in particular.

Jordan Peterson on Solzhenitsyn’s growing relevance

A good indication that Solzhenitsyn’s relevance grows is the great interest shown in him by Dr. Jordan Peterson, a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto and the author of the multi-million copy bestseller 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Judging by what Peterson has to say in his recent podcast with Jocko Willink, Solzhenitsyn’s works provide one of the strongest antidotes to chaos increasingly besetting our world. As Dr. Peterson points out, one of the reasons for the chaos is that Pol Sci profs in the West tend to be “under the sway of Marxist thinking”. Not for nothing, Dr. Peterson is behind the new edition of The Gulag Archipelago. The latter is one of the 15 great world books he recommends, while two others belong to Solzhenitsyn’s favorite Dostoevsky.

From Solzhenitsyn to Putin

Friedman is right that “the intellectual foundation” for Vladimir Putin’s Russia was, to a large extent, laid thanks to the influence that Solzhenitsyn exerted on the president. You can read more about that influence in my 2016 interview with Jonas Alexis carried by Veterans Today, a site founded by former US military officers who are now critical of US foreign policy. In that Interview I mentioned that I had foreseen Russia’s return to its Christian roots in my 1991 book Russia Beyond Communism: A Chronicle of National Rebirth. In fact, the book was dedicated to the Millennium of Russian Baptism in 1988. At that time Soviet soldiers were forbidden even to wear a crucifix or any other religious symbol.

“Now, if you watch the military parade on the 9th of May, Victory over Germany Day, you will see on Russian national TV how the commanding General Sergei Shoigu, Russia’s Defense Minister, crosses himself publicly before he enters the Red Square through the Kremlin Gate. If you did not see it, I am not surprised. The Big Media indulges in Putin-phobia to divert attention to the greatest event of the past 25 years, Russia’s spiritual rebirth, of which Putin and Shoigu are just two examples”.

Of course, the process of Russia’s spiritual rebirth was very uneven during the Yeltsin era. After returning to Russia in 1994, Solzhenitsyn was at pain witnessing the loss of the country’s sovereignty after the neo-liberal “shock therapy” reforms were set in motion with the assistance of US government. That “assistance” was perhaps best described by professor Janine Wedel in her book 2001“Collision and Collusion: The Strange Case of Western Aid to Eastern Europe”. In December 1998 Solzhenitsyn publicly repudiated Yeltsin’s “reforms” by refusing to accept the highest national award. As president of RAGA, on March 17, March 1999, I sent to President Clinton an Open Letter on the Russian Crisis demanding to stop interfering in Russian affairs. The letter was signed by over a hundred of prominent Americans and carried by Johnson’s Russia List, an alternative site for unbiased information about Russia. Clinton’s reply was evasive but polite.

With Kevin Barrett: The USA and Russia trading places

In November 2017, I had a video interview with Dr. Kevin Barrett. He is not just a literary scholar familiar with the works of Mikhail Bakhtin but also a fellow dissident in the USA. He described me as a former Soviet dissident and defector who now “wonders whether Russia and the United States have switched places: Now it’s the USA that surveys its citizens, doesn’t tolerate dissenting voices, and insists on inflicting its mendacious official perspective on everyone, everywhere; while Russia has left Communism behind and emerged as a pluralistic nation, whose worst “crime” (according to the Masters of the Universe in Washington) is allowing Western dissidents to reach a larger audience via RT and Sputnik”.

The interviewer asked: Is the USA becoming monologic and totalitarian? [64]Yes, I replied, it appears that “Russia

and the United States have switched places”. But, to be fair, the situation in the States is not yet totalitarian. But regrettably there are unmistakable proclivities toward more monologism in mass media and toward one or another form of totalitarian rule.

Chantal Delsol calls Solzhenitsyn “liberal conservative”

Recently, Chantal Delsol of France argued that Solzhenitsyn is far from a reactionary, as some people called him in a derogatory rage. Delsol rather sees Solzhenitsyn as “liberal conservative”. According to Delsol, Solzhenitsyn has already played a salutary role for France as he gave “a vivid lesson for the history of France, for the younger generations. Let them never forget that abyss of lies into which our society fell: there were an impressive number of Frenchmen who glorified the Soviet regime, while dissidents like Solzhenitsyn lived in fear. Here, in France, everything was done to deny Soviet reality. I will never forget what false arguments my uncle, a French communist, was trying to make me believe that the GULAG Archipelago was written by the CIA.”

As to Solzhenitsyn’s contribution to Western civilization, I remember reading some early articles of Professor Richard Tempest, who also gave a paper "Solzhenitsyn contra Lenin” at our Vermont forum. In the early article he listed Solzhenitsyn in the same league with such European cultural heroes as Goethe, Schiller, Nietzsche and Byron.

As I have shown above, the Russian philosopher Kholmogorov is even more emphatic in stressing Solzhenitsyn’s global reach as well as the need for Western theorists to see the West’s limitations:

“Solzhenitsyn’s legacy is not only a Russian, but a planetary political phenomenon. It was Solzhenitsyn who in his famous Harvard Speech warned the West that they were not alone on this planet, that civilizations described by Western historians and culture theorists are no mere decorative elements, and instead living worlds in themselves, that cannot have a Western measure imposed upon them. Russia, a unique civilization, is of these historical worlds… This very idea has constituted the bedrock of Russian foreign policy since Putin’s Munich Speech in 2007.”

The best summation of Kholmogorov’s article was made by one of The Unz Review attentive readers, AaronB :

<<A return to religion in some form, not necessarily Christianity, but an appreciation for the numinous and the supernatural that underlies all phenomena and the unseen bonds that unites everything (see quantum mechanics), a return to a moral vision and away from mere instrumentalism, a turn away from individualism and towards appreciation for communal life and the rebuilding of social capital in the form of a unifying culture and sense of shared destiny, identity, origin, and purpose, the renewed appreciation for the aesthetic world view, art, poetry, myth, and legend, and the reduction of logic and rationality to important but limited instruments and as not providing unique access to ultimate truth, based on Kant’s demonstration that logic consistently applied ends in absurdity and contradiction, and retaining scientific and technological development but reducing their importance and firmly subordination them to a scale of human values….>>

In a number of crucial respects Kholmogorov unwittingly reiterates Bakhtin’s arguments against the excessive rationalism of the age of Reason and Enlightenment while justifying the need for Dostoevsky’s polyphonic artistic strategy. It was way back in 1929 and then again in 1963 when Mikhail Bakhtin challenged “the monologic principle as the trademark of modern times.”

Ron Unz on the need to accept the whole of Solzhenitsyn

It is very ironic and bad for America that its mega media establishment turned a deaf ear to Solzhenitsyn’s genuinely liberal commandment to always pay attention to polyphony of different political persuasions and engage opponents in a friendly dialogue. “For decades most Americans would have ranked Nobel Laureate Alexander Solzhenitsyn as among the world’s greatest literary figures, and his Gulag Archipelago alone sold over 10 million copies,” says Ron Unz, the publisher of the most remarkable alternative web-journal The Unz Review. [69] “But his last work (Two Hundred Years Together) was a massive two-volume account of the tragic 200 years of shared history between Russians and Jews, and despite its 2002 release in Russian and numerous other world languages, there has yet to be an authorized English translation, though various partial editions have circulated on the Internet in samizdat form”. This lack of a dialogue among Americans as a social arrangement is very deplorable indeed. No wonder the US government eschews a dialogue with Russia.

I think the man to whom America gave a refuge and freedom to write and who enjoined all of us “Do not live a lie” deserves that First Amendment to US Constitution is fully applies to all his work without exception.

Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century

Even while American publishers were reluctant to publish Solzhenitsyn’s 2002 book on Russian-Jewish relations, Yuri Slezkine’s pioneering book “The Jewish Century,” published in 2004, largely confirms Solzhenitsyn’s contention that Jews played a very prominent role in the Bolshevik revolution. Professor Slezkine is extremely ingenious in challenging us to think about a variation of religious patterns, geographic and historical circumstances that contribute to a variety of national responses to the challenge of modernity.One way or another, Slezkine boldly asserts that "The modern era is the Jewish era, and the twentieth century is the Jewish century".[72] This is not the place to discuss his book, but it's easy to agree with the publishers that this is “one of the most original and intellectually provocative books on Jewish culture for many years.” Slezkine brought the Jews out of the ghetto of exclusivity by conditionally dividing the whole of humanity into Apollonian people, named after Apollo, the Greek god of reason and the settled life, and the admirers of Hermes, the Greek god of craft, mediation, commerce and, it’s no secret, trickery. In the Roman Empire, Hermes expanded his territory under the name of Mercury. Slezkine’s book implicitly repudiates the Marxist denial of the importance of national character and specificity of each ethnic group in the overall history of mankind.

Because of the inherent dogmatism of pseudoscientific Marxism-Leninism, the topic of different national characters and types of behavior was renounced in the USSR as “reactionary” and contrary to the spirit of “proletarian internationalism.” But without this topic, one can hardly understand what happened in Russia in 1917. Certainly, the writings of Solzhenitsyn, as well as Slezkine’s, pave the way for further research of the subject and its objective evaluation on a global scale. Let me refer the reader to my earlier essay “Emperor Michael II in the Solzhenitsyn House” where I discuss this topic in some detail, including my disagreements with Solzhenitsyn.

Spiritual Realism

Could not then art and literature, if exercised in Solzhenitsyn’s footsteps, offer a very real succor to the modern world?

When I was writing my Ph.D. dissertation on Solzhenitsyn, one of my favorite authors on the topic of how Westerners approach Russian literature was George Steiner, especially his volume Tolstoy or Dostoevsky. Steiner pointed out that both writers “exercise upon our minds pressures and compulsions of such obvious force, they engage values so obviously germane to the major politics of our time, that we cannot, even if we should wish to do so, respond on purely literary grounds”. I think this is no less true of Solzhenitsyn.

But then Steiner tells how some White Russian émigré were thirsting of a “new religious idea: who believe that in a fusion between the thought of Tolstoy and that of Dostoevsky will be found the Symbol, the Union, to lead and revive.” I believe that such a fusion between Tolstoy and Dostoevsky manifested itself in the art of Solzhenitsyn: it has Tolstoy’s historical sweep and Dostoevsky’s psychological insights expressed through polyphony of its diverse ideological heroes. I have called this fusion spiritual realism.

People to People Diplomacy

On December 10, 2018, while I was writing this article, I made a break to attend the International Conference of Scholars to celebrate Solzhenitsyn’s Centenary in Moscow. It was a sign of time that it took place in The Russian State Library which several generations of Russians had known as The Lenin Library. Now the name of the first Soviet leader is chiefly confined to his Mausoleum on Red Square. Natalya Solzhenitsyn, the writer’s widow, was the first speaker. “Today we celebrate 100 years since Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born. Tomorrow, on December 11th, the Second Century of his life will begin”. She was interrupted by a round of healthy applause.

I firmly believe that Solzhenitsyn’s writing will bless and endow the 21st century in Russia. I also hope it will endow the United States. After all, the major part of his works was researched and produced in the USA. This obliges all his devotees in both countries, as well as in China and the rest of the world, to take seriously his call for “Repentance and Self-Limitation in the Life of Nations” he issued way back in 1973.

“Today, as never before, a Christian initiative is needed to counter the godless humanism that is destroying mankind. … We are too passive. … We do not carry our own religious will. … We seem to have forgotten that we have been entrusted with the great task of transforming the world. … We need new creative efforts, we need a new language. We must speak of what is beyond modernity, of what is eternally living and absolute in this world, of what is simultaneously both eternally old and eternally young. It must mean not only a breakthrough into eternity but the presence of eternity in our own time. … It must lead not to a reformation but to a transformation of Christian consciousness and life, and through it to a transformation of the world.”

It is not an easy task. But, in the face of threat of war that might destroy all life on the Planet Earth, no task, no matter how hard, should be viewed as “unrealistic” or not worthy of trying.This is not just relevant but highly urgent for both the USA and Russia, the two leading nuclear powers, to hear for Solzhenitsyn’s call.

Margo Caulfield’s Letter to Russia

Let me conclude by pasting the letter that the people of Cavendish, Vermont, sent to the people of Russia, the letter that Natalya Solzhenitsyn shared with the audience in the Russian State Library conference on December 10, 2018.

To the People of Russia:

For 18 of the 20 years he was exiled from Russia, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and his family lived with us in Cavendish, Vermont. The Solzhenitsyns were then, as they are now, good neighbors, respected and valued members of our community. While we are sad when residents choose to leave, we were glad that Solzhenitsyn was able to return to his “motherland,” as he predicted he would at our 1977 Cavendish Town Meeting. No matter how much our countryside may have reminded him of Russia, and allowed him the time to write, it would never compensate for the country he cared so deeply about. Solzhenitsyn’s values were a good match for our Yankee way of life-hard work and the ability to speak freely and openly, yet also respectful of others and their privacy. While he learned from us how grass-roots democracy works, we in turn were reminded of the importance of providing sanctuary to those in need and the value of having courage and strong beliefs. Upon his departure, Solzhenitsyn left the town not only autographed copies of his books, but more importantly, a homestead which allows his children to remain an integral and important part of our community. The lessons he instilled in his sons are shared with us as we work together to resolve the thorny issues of 21st-century life. Every town needs a secret, such as the one we kept: “No directions to the Solzhenitsyn’s home,” as it united us for a common good. We still do not give out directions, but we do welcome visitors from around the world. On this the 100th birthday of Solzhenitsyn, the people of Cavendish extend our best wishes to the people of his homeland.

On behalf of the people of Cavendish, Margo Caulfield, Director, Cavendish Historical Society Brendan McNamara, Cavendish Town Manager

As an act of People-to-People diplomacy, this letter has reaffirmed my faith in America which once gave me a refuge and hospitality but now appears to be less civil at home and more war-like abroad than it was when my Russia was in the grip of totalitarian Communism. Solzhenitsyn, more than anybody else, unites Russia and the USA in their urgent task and duty to secure a peaceful, free, fair, and harmonious global commonwealth in which every nation is a proud member.

Dr. Vladislav Krasnov (aka W George Krasnow), former professor and head of the Russian Department of the Monterey Institute of International Studies, who currently runs an Association of Americans for Friendship with Russia, RAGA (www.raga.org). He is the author of Russia Beyond Communism: A Chronicle of National Rebirth («Íîâàÿ Ðîññèÿ: îò êîììóíèçìà ê íàöèîíàëüíîìó âîçðîæäåíèþ»)

December 15, 2018, Moscow© W.G. Krasnow, 2018

Up

|